"The ride you are about to tackle is challenging at times but is not a test of skill - however it has defeated many experienced riders that got too cocky. India can be an unpredictable and at times dangerous place to ride but in terms of reward it is unparalleled - en route you can literally gauge your rexperiences by the minute. Many people have their lives entirely changed during the rally and it is fair to say that most of you will have at least your view on life changed by this trip."

"The Country

India. Indiaaaahhhh."

EnduroIndia Roadbook 2007

It is now three weeks since I got back from riding in India, and I still have an impression on my left and right forearms of the tight-fitting armour shirt I wore during the trip. Maybe…, I thought - maybe my skin is losing its elasticity. Maybe, I’m beginning to turn into an "old person". I did a quick calculation: in the year 2012, I would become eligible for a senior citizen bus pass. That scared me. Growing old was never in my game plan. I began to feel glad that I hadn't put off doing this trip for another year.

How many years of riding and travelling did I have left?

That wasn't an idea I was ready to confront right now, and probably not for some time to come. I was still getting over two terrible years of discovering what it is like, suddenly and unexpectedly, to run out of time.

OK, I decided. That's enough!

So I started to think about something else - about my next bike trip.

I'm at a crossroads in life. I have no ties, nothing to hold me down. I can do more or less anything I want - anything! What I want to do is to travel. I've had loads of thoughts about where I want to go and what I want to do. But wherever I go, whatever I do, it has to include a bike. These days, I can't imagine life without one.

In the last six months I've been doing some heavy fantasising about all the places I want to see. Right now, though, I just want to go back to India. I want to go on my own. And I want to go soon. I need to know if the 2000km journey I have just taken through its southern states - through its mountains, jungles, forests and towns - was real or just a dream. Because that what is seems like - a strange, impossible waking dream.

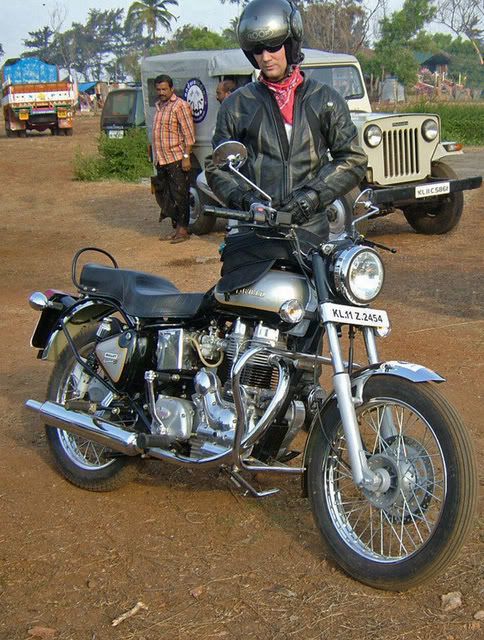

It wouldn't take much to go back. You can hire a Royal Enfield Bullet motorcyle in India for £7 a day. Petrol is dirt cheap. I know I could live very well on £80 a week. And, I've now got some familiarity with the place - well, at least, I think I have. India is huge, varied, beautiful, filthy, colourful and incomprehensible. It's everything that people say that it is. It’s overwhelming.

How familiar is that?

Earlier this year I flew a third the way round the world with 130 other bikers for eleven days of hard riding through some of the most spectacular scenery I've ever seen and on what must be some of the craziest roads on the planet. India is alien in an oddly comfortable sort of way. It has left me still struggling with a headful of confusing images. I don't suppose, though, that India could ever be put into order. It's not that sort of place.

To my European sense of geography the landscapes, the culture, the climate and the sheer variety of the sub-continent are too huge to be truly comprehensible. But, to an Englishman, India is also familiar: Indians drive on the left (more or less), English is widely spoken and understood, good curry restaurants are not difficult to find, there is an Indian grocer on ever street corner. Everyone understands cricket. It's just like home. And apart from all that, the fundamental preoccupations of Indians are no different from those of other people wherever they may be.

At first, I had some preconceptions to deal with. India looms large in the British imagination especially for someone of my generation. Whatever I might think of the empire now, India was part of my early consciousness - a vague part maybe, but still a part. When I was a kid, most British coins carried the abbreviated latin phrase, Ind Imp (emperor of India) around the king's head, news items about India were regularly broadcast by the BBC (much more frequently than news items about Europe), and I grew up reading exotic tales of the sub-continent in dozens of story books.

It's not surprising, then, that before I left England I had some very strange, half-unconscious notions of the place. I flew out of Heathrow with a mental image of India that was as exotic and mysterious as anything in a nineteenth-century picture book. I imagined a land that smelled of spice and twanged to the sound of sitars. I knew that Indian air would be a strange and mysterious thing to breathe. The country would be more fabulous, more colourful and more exotic than Europe in every way.

What I found was a bunch of people going about their daily business: riding their scoots; digging their fields; repairing their houses; raising their children; trying to make a few rupees – or ten million of them - by any means at their disposal. It wasn't so different to anywhere else I has been. Life in India is practical, dumb and routine. Its people are kept busy dealing with the very ordinary demands of material existence.

But, now that I'm back home and have seen the ordinary, everyday India with my own eyes, I still can't quite bring myself to believe in it. Yes, India is down-to-earth and familiar. But its familiarity highlights just how strangely different it is: Indians live by a complex set of values just like us, but they are very different values; they worship and pray to similarly bizarre gods, but they are different gods; they live a life governed mostly by habit, but their habits are very suprising to a Westerner.

And there is one difference above all others that distinguishes their lives from ours: Indian people have not lost their ability to be happy or to enjoy themselves. In England, that ability has declined noticeably in my lifetime. The more consumerist we become, the unhappier we get. You see a common emptiness reflected in people's faces as you pass them on the street. You see it in pubs and restaurants, in shops and offices and, worst of all, you see it in your own home. In India, things are different. In India there is always a smile. At any moment, in the most unexpected of circumstances, on the dustiest road, in the midst of the direst poverty, there is always the opportunity for a smile.

India is still an open-air, very public kind of place. Lives are lived out of doors, and you are never very far from the humm and buzz of communal existence. It's an earbashingly noisy place. (One in six human beings alive on this planet today is an Indian.) For people who have nothing - and often that is literally true - relationship is everything. Service to others is still a joy, and life, it seems, is worth the living.

Two women from the village of Sanyasipura

As hard as I think about it, though, I'm still unable to explain how I really feel about the place. If I start to tell someone about my experience, I get very excited. But before too long I've run out of words and a sense of frustration and puzzlement sets in. I know what I feel, but the words which come out of my mouth make my journey sound like a trip down the road to the local chippie. And I guess that is the truth of the matter. India is both very ordinary and very extraordinary at the same time. The effect it had on me is similar to the effect my armour shirt is having on my arms. It has left a deep and lasting impression but for reasons that I can't explain.

Even though I still find the place a puzzle and am struggling to articulate my feelings about it, I'll have a go. And I suspect that what I write here will surprise me as much as it may anyone else.

Everyone in India wants to have their phtograph taken

There is no real centre to this country, no real place to start describing it. It is beautiful beyond belief, disorganised, riotous, drab, colourful, naïve, sophisticated, innocent, shockingly corrupt, elevated, venal, bureaucratic, and vast. It has immense plains and high mountains, enormous rivers, forests and jungles. It has rice fields and rubber plantations. There are tea bushes and coffee bushes, spice groves and coconut trees, bullock carts, street vendors, elephants and tigers, ascetics and con-men, suffering and indifference, spiritual freedom and bonded slavery, mad truckers and holy cows.

I can’t get over the cows. Cows, of course, are sacred to Hindus and are allowed to wander about wherever they want. They house the souls of human ancestors and must not be harmed. I knew all this before I went, but until I saw them moving through the city streets like some strange law of nature, eating rubbish from the gutters or food from the stalls, or munching at the floral garlands on my bike… until I saw them, I did not really understand.

Cows just loved the garlands of flowers which decorated our bikes.

The reverence Hindus show for these slow, docile beasts is a constant reminder of everything we busy Westerners have lost. Think of the most ingrained rules of our civilisation, our values and conventions, our most powerful institutions. Think of property, money, law, justice, labour, precedence, hierarchy, status, power, force, government. The great sleepy-eyed beasts know nothing of these things. Their lives are governed by a peaceable anarchy of the soul, wholly unidiverted by human rules or institutions.

They wander through private human gardens; they hold up human traffic; and they poo in human streets. They make their meditative way down busy thoroughfares through seas of smoothly parting traffic. They eat fruit from a vendor's stall, and the vendor appears not to notice. The whole of the country adapts itself to their smallest acts. Each time you see a cow in India you also see the normal rules and habits of human society momentarily suspended. By being what they are and by doing what they do, cows crack open the moulds of social convention. They liberate the mind. They give us a glimpse into a world of social freedom that we can hardly imagine. I can't really explain. You have to see this happening for yourself.

Molem. A dusty truck stop village in Goa state.

My first impressions of India were simple and immediate: it was hot, dusty, dirty, paranoid and poor. And all that hit me before I’d cleared Immigration at Goa airport.

Going through Immigration was an special experience in itself. The moment I stepped into line a young woman approached in an elegant sari and handed me a form. To my list of first impressions I now added, ‘bureaucratic’ and ‘confusing.’ I’ve never travelled anywhere before where I was required to fill in so many forms to so little apparent purpose, or where those forms were checked so many times by so many frosty-faced men and women in military-style uniforms.

And maybe they were the military. Goa airport, the main entry point to one of India’s prime tourist destinations, also appears to double as some sort of military base. Row upon row of helicopters and planes in camouflage colours lined the exceptionally long runway. And there were signs everywhere saying ‘No Photographs.’ Not that there was much you would want to take a picture of. The airport terminal was shabby and run-down. It's wood panelling was dessicated by the heat. The Baggage Reclaim carousel wheezed alarmingly. The air conditioning rattled.

I collected my luggage and queued at a Bureau de Change next to the carousel. It is illegal to export Rupees out of India so you have to change your money once you are inside the country. As I stood in line, another word spontaneously added itself to my growing list of adjectives. The word was, 'bizarre.' Watching the transactions taking place ahead of me, I began to realise that though the bureau had run out of large denomination notes, it was still breezily doing business.

The company I had travelled with had recommended that we could live very well on £300 for two weeks. So that's what people in front of me were asking to change - £300 each. In return for their English money, the bureau was handing out bundles of 10 Rupee notes. Ten Rupees is worth something less than 10p (or a little more than a US dime). I'll leave it to you to work out how many 10 Rupee notes you would get for £300 ($450). The money came in big blocks of banknotes about the dimension and colour of a standard house brick, close-wrapped in polythene and, just for good measure, held together with a huge staple driven through the centre. A queue of confused looking Brits were leaving the airport laden with so many bricks they could probably add a sizeable extension to Government House in New Delhi.

Fortunately, before I got to the window, an excited looking man burst into the back of the booth brandishing a box containing a new supply of notes. Well, perhaps it was fortunate. Perhaps not. In exchange for my £300 I was handed a more reasonably sized wad of 1000 rupee notes (worth about £12.00 each) and a selection of smaller deonominations. This proved to be something of a problem later as many shopkeepers in the more rural areas were struck dumb at the mere sight of such vast sums of money.

At the airport exit, a pair of military guys were collecting the final counterfoils from the oddly functionless forms we had filled in earlier. It was a strange job for heavily muscled, armed guards in sharp khaki kit and army berets. Their uniforms and neatly clipped moustaches bristled with importance and just a little menace. They stood, wooden and erect, like a line of sentinels guarding the gates to another world. And beyond them lay a different India, a different fragment of this hugely fragmented country. It was neither stiff nor bureaucratic but utterly chaotic! Beyond the doorway, eager young lads in floppy airport uniforms fought each other to help us to get our luggage to the waiting buses. EnduroIndia staff hovered around the entrance giving the same advice to each of us as we passed. “The busses are up on your left," they said, "Don’t let go of your luggage.”

I was bleary-eyed from 48 hours without sleep, a 14-hour flight, and a strange in-flight dinner. I was feeling too tired, too grouchy and far too ana to feel appreciative of all this sudden hyperactive confusion. So I just did as I was told. I clung blindly to my trolley (as did my three bickering helpers) and attempted to steer my own course towards the busses.

Fortunately, the wildly different directions in which my arguing helpers were attempting to steer my luggage trolley cancelled each other out and I managed to keep a straight course without too much difficulty. The moment we arrived, the three lads ceased their argument and their faces lit up with three brilliant smiles of success. Without even glancing in my direction, they turned on their heels and hurried off without another word to bestow their services on another ignorant and helpless traveller.

Uncertainty at Goa airport. The guy in brown, by the way is 'Ben' who only took his motorcycle test

a month before flying out to India. And until he arrived he hadn't ridden since.

Later, I learned to appreciate the very real and highly spirited nature of the Indian desire to help. And I came to see all this kindness-induced chaos as a symbol for the way this extraordinary country manages to function. For function it does, but not by any Western logic. At a purely selfish level, I hope it never changes. It is all part of the joy and mayhem of the place. It’s fun, it works, and it is (usually) very good natured - until it isn't. And then you have to watch out. Swim with it, and the Indian way of doing things is actually far less stressful than the mechanically ordered systems we have in The West. But you must flow with the current. Fight it, and this continent will chew you up and spit you out like a load of old cardamon pods. Its way of doing things is inimitably its own, and it is as remorseless and irreversible as the waters of the Ganges.