22nd Feb

Day 2 of the Rally

Start: Beach Huts on Palolem Beach (Goa)

Finish: Om Beach at Gokarna

Distance: 210 km.

“The second day is longer and more demanding but feels no harder due to the fact you are becoming more confident on your bike and the forest trails and mountain passes are becoming less daunting. Today’s ride is quite simply mind-blowing as we wind our way on and off road all the way over the mountains and back to our night’s stop point at a truly secret cove, looking out to the Arabian see. Tonight the accommodation is packed tight and hot.”

From

The EnduroIndia Roadbook 2007

I said goodbye to my hut (I’m a sentimental soul), turned my back on the lazy life of Palolem Beach and headed off into the palm forest to find ‘Beast’ (that’s ‘Beast’ as in, ‘Beauty and the Beast’) - my bike, my Royal Enfield Bullet and began to think about the day ahead.

I was looking forward to today's ride. This was going to be the first big ‘off-roading’ day of the rally – and the first time I had done any ‘off-roading’ of any kind. The idea of riding forest tracks in India sounded to me like heaven, one big adventure wrapped up in another. I have to admit that there was a nervous tremor in my belly as I walked out towards the bikes that morning. But like all other feelings and thoughts it was being swamped out by a flood of excitement.

‘Off-roading’ is what everyone was calling it but in fact, we were going to be riding on 'roads' all day today. It's just that, like everything else in this amazing country, the definition of a ‘road’ is very broad. It is applied equally to a National Highway and to the strip of semi-passable ground we would be taking through the hillside forests near Bare (pronounced

Bar-ray).

Once, long ago, this ribbon of sandy soil had been a proper road, with a proper surface to it, but no-one had travelled it, except on foot, since the time of the British Raj – not until the EnduroIndia Crew discovered it and got permission to open it up again. Simon included it in the route for the first time last year. It had taken The Crew four years to get it into a rideable state. And even after all their work, it is still no more than a rough track.

I had no idea how well I was going to manage to ride on this sort of surface - I'm the guy who gets nervous riding over his mate's gravel drive. But I reckoned I’d soon find out. I was up for a challenge, and off-roading sounded like fun. Many years ago I discovered an important principle: if I wanted to do something badly enough, there was no point thinking about it. I just had to get out there and stand on the starting line. Once I had got that far, I was unlikely to turn back. And doing it that way, I enjoyed the experience all the more for not having a head full of pre-conceptions about it. I'm cautious (and lazy) by nature and if I hadn't learned that bit of wisdom early on, I'd have led a much duller life.

The way the Enfield had coped with the dusty lane the previous day had given an extra boost to my confidence and I was looking forward to something meatier. I wanted to have a few emotional highs on this trip and I was expecting this to be one of them.

People finished wolfing down their breakfasts in the beach cafe and assembled by the bikes. Simon called for hush and everyone gathered round The Crew (sort of) for the morning ‘briefing,’ which, because it was delivered by Simon, wasn't all that brief - but it was entertaining. Over the next ten minutes we got the usual advice about not travelling alone (

), a short description of the day’s riding (

), and a few wild tales from the Simon Smith archive of Indian adventures (

).

It was during this morning’s meeting that Toby first came to everyone’s attention by winning the ‘Dick of the Day’ award. It was inevitable, like a law of nature. Toby, with his tangential take on life was simply wired up to get himself into a pickle. By the end of the rally, then, no-one was surprised that he had won the award several times.

He had come out to join the rally with his mate, David. Toby and David quickly emerged as two of the ‘characters’ on this year's rally, a spectacularly entertaining double act who were rarely off everyone else's radar. Love 'em or hate 'em, you couldn't ignore them. In the coming weeks, their experimental approach to almost everything livened up the days’ riding and provided much of the evenings’ entertainment.

Toby

Toby

Simon had overheard a conversation the previous night through the thin plywood walls which divided the beach huts. In the neighbouring hut David and Toby were almost helpless with laughter as they talked over the day's events. Toby had brought his sleeping bag to Palolem on the bike with him, as we all had. It was a bulky, old-fashioned looking bit of kit, which he had bought at the last minute. It had taken up a lot of his luggage allowance on the flight and, yesterday, had been a nightmare to get here because it kept falling off his bike. (David had carried it for a while, and it kept falling off his bike, too.) Last night, Toby had unrolled his sleeping bag for the first time, to discover, much to his surprise, that it looked less like a sleeping bag and rather more like a blow-up rubber dinghy.

After the briefing, people went back to their bikes and kicked them into life for the day’s ride. A beautiful and very distinctive roar began to reverberate through the palm forest. Listening to the sound of one-hundred-and-fifty of these elegant little machines rumbling in unison was enough to put a zing in anyone’s blood. I stood there loving everything about this trip so far. And especially the sturdy little Enfields – though they weren't quite so ‘little’ in my imagination any more, now that I'd had time to discover what brilliant machines they were. I looked around for Larry, but he was parked much further back. I would have to wait for him once I got out onto the road. But for now I nudged forward to get a better placing for an early start, and wedged myself in among those close up to ‘poll position’ (competitive? Me?) .

While I waited for the off, I glanced back through the trees to see if I could catch a last sight of my hut and the long line of the beach. I wanted to fix the scene in my memory. I’d really fallen for this place. I could see myself coming back here some time in the future and chilling out. As it turned out, I wouldn't have to wait very long to see my hut or Palolem Beach again. Three weeks later, back in England I was watching the opening sequence of the latest James Bond film - and there it was: my hut! large as life, snuggled up against the edge of the trees, with JB racing past it in full pursuit of someone or something.

One of the crew members was suddenly pointing and waving his arms. I had no idea what was going on. The bikes in front of me started to move over to one side or another, leaving me a clear line onto the track ahead. Nothing was coming up from behind. I hung back for a few seconds then, in a moment of impulse or impatience, went for it, kicking the Bullet into gear and riding down the quarter mile of sandy, winding paths among the beach huts and shacks to the main road. At the road, I looked back. Nothing. No-one had followed. I was alone. Whoops! So I parked up, and chatted to the film crew positioned near the gates and waited with them for the 'grand exit of bikes' - which didn’t happen for another ten minutes. It was the first and only time on the rally that I was anywhere near the front.

I slowed to let others ride past till Larry came by and then set off with him at a fair pace down the narrow country roads. Houses and people crowded in on us thickly. India is densely populated and coastal Goa is no exception. Villages followed one another with hardly a break between them along the roads. On either side of us locals were coming and going, walking up and down. Children, togged up in immaculate uniforms, were making their way to school. Small family houses were interespresed with very impressive looking villas or recently built blocks of flats. It was all very dusty and, in places, a bit thrown together; the roads were cracked and potholed but Goa has the smell of modest propsperity about it. So far I'd seen nothing approaching the extreme poverty you see in Oxfam adverts.

I hadn't ridden far through all this buzzing human activity, when I met the front riders coming back towards me. I never did find out for sure what the road blockage was up ahead of us, but it meant a detour. I turned back and followed the rest. The detour was no big deal in itself - just a matter of a few kilometres - but it totally screwed up my maths for the rest of the day. ‘Beast’ had started out that morning with exactly 2,350 km on the clock. This made calculating distances from our starting point very easy - which was all to the good as I had a mild hangover that morning and I am totally incapable of adding up when I have a hangover. The detour meant that I had to recalibrate. My effective starting figure when working out distances on the route map was now 2,357.4 km. But 2,357.4 km is not so easy a figure to calculate with - or even bloody well remember. Damn! Until the Kingfisher-induced fug wore off that afternoon, I was going to have extreme difficulty in working out where I was.

Twenty km out from the hotel, we passed a petrol station, and to judge from the number of riders who had pulled into its forecourt, it seemed that most of us had forgotten to fill up the night before. I had a fairly full tank but I wanted to check my tyre pressures, so I decided to find the air pump and thought I might as well top up with petrol at the same time.

The owner of the filling station had a gleeful and slightly mad look in his eyes - as well he might. He was running back and forth between the office and the pumps carrying wads of notes. He was having a good day. There were four pumps on the forecourt but there were only two attendants and it seems it takes two attendants to fill a single bike in India. The queue moved slowly, but as always, it was a lovely morning, and no-one but the front runners felt in much of a hurry - and the front-runners were long gone.

The youngsters operating the pump made a great thing of pointing out to us that the gauge read ‘0’ before they started filling the engine. Clearly they were familiar with the Western belief in the wholly dishonest nature of all ‘foreigners’. But the task of filling our tanks was carried out quietly and smoothly. When it came to pumping up my front tyre it was a different matter. The queue for the air pump was not so long, but inflating tyres was clearly a more complex process. It took four grown men and a lot of shouting and waving of arms to ensure that my tyre was correctly inflated. In a country with vast levels of unemployment, you often find this kind of ‘job-sharing.' Wages might be low but at least everyone has something to take home to the family at the end of the working day.

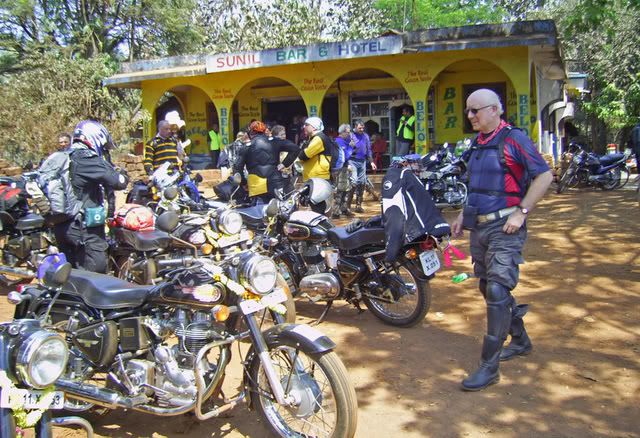

A long wait at the Oil India petrol station. You get the impression that most Indians

A long wait at the Oil India petrol station. You get the impression that most Indians

do not understand the meaning of a word like 'hurry.' The guy in the balaclava near the lampost

is Andrew, one of the doctors. At home he volunteers as a speedway medic.

Another six kilometres up the road we ran into the border check post. We were about the leave the tiny tourist state of Goa and enter Karnataka - ‘Real India’ as someone described it. Goa is relatively europeanised and the lack of serious poverty has a lot to do with the tourist trade. I was told that once we crossed over the border, that would change.

The check post was no more than an informal barrier across the road - permanently raised - with a sleepy attendant in military uniform standing beside it. It was there just to make a point rather than stop the traffic. What I wasn’t expecting was the reception committee on the other side.

About twelve guys in formal business wear – immaculately pressed striped shirts and well-creased trousers - were standing in a row, supporting the poles of a huge banner. Several others were holding up a smaller banner at waist height. Both banners read, “Welcome to Karnataka.” As each car or bike passed through the barrier a portly chap with a mature beer gut stepped forward, wreathed in smiles. “Welcome to Karnataka, sir,” he would say, repeating the mantra for what was, no doubt, the umpteenth time that day. And as he made his greeting, he presented the driver or rider with a single red rose. Like Larry and Hash and most of the other Enduros, I had bike gloves on. So, with the most meticulous care, the guy leaned over and attached the rose to my armour, before standing back and waving me on.

My guess is that he and his fellows were members of the Karnataka state tourism board. We came across a number of such worthies in the different states we visited. I was very tickled by this greeting. It was just so… Indian! I tried to imagine a reception committee of Round Table small-time businessmen waiting for me with a budding rose as I crossed the county border between Hertfordshire and Bedfordshire back home in England. “Welcome to Bedfordshire, sir," they might say ("Enter our beautiful county and spend lots of money.") No. No way! It wouldn't happen like that. The most you might find would be a couple of locals leaning over their fences shouting, “Bloody bikers; bugger off back where you came from.” That would be more like it.

I was in a very happy mood as we rolled down the wide open highway beyond the barrier. Larry, and I were riding at a lazy 45 km per hour. We crossed a bridge over another broad, palm-fringed river, took a sharp 300 degree turn, rode along beside a canal then ticked along down a tiny tarmac road at 10 miles an hour. The road ran right through the neat and tidy village of Idgundi. It was so narrow I was sure I was going to hit something - or someone. We squeezed our way past old men and sacred cows, sleeping dogs and excited children. Small inconsequential details took on a strange significance and lodged themselves in my memory: a busy, staggered junction; an old man with a stiff leg; a tumble-down grocery shop; two women in a telephone hut; the vivid blue of a wall; the doleful eye of a cow as it ambled past. All these details flashed brilliantly for a second into my consciousness before melting away into memory. They seemed no more than expressions of the bright, sunlit world around me, part of my happy mood. A bit of me wanted to stop the bike, to talk to people, to move closer to their lives and to the things that they made their lives out of, but the rest of me carried on riding. I knew that if I stopped, even for a second, and engaged my mind with detail, the spell would be broken and my blissful but delicate mood would be shattered for good.

Detail aplenty broke in on my thoughts at the next turning which took us back (briefly) onto a busy road and demanded total concentration. The world changed abruptly. The flow was gone, but my happiness remained. We followed some lovely twists and turns on a beautifully cambered road that swung gracefully downhill, through sparse and delicate woodland.

Well I've got to fess up to this one. I've never carried much weight, but I lost a lot more in India

Well I've got to fess up to this one. I've never carried much weight, but I lost a lot more in India

thanks to having to eat a lot of things I am allergic to. It happens every time I go abroad. So this is me

looking like a 15 year old boy.

The world changed again, and we were riding on narrow, poorly surfaced country lanes sweeping along among grassy levels and bits of scrubland. A broad river came into view, and flowed beside us, almost lapping the road. Here and there it briefly turned away or widened into empty marshland. We stopped among a lonely, watery landscape to look about us and take some photographs. A solitary woman in a brilliant red and yellow sari crossed a distant causeway among the river channels. And around her - flowing water, open sky, a little solid earth and the infinitely mournful cries of river birds.

Further up the road another Enduro had stopped and was gazing silently at the view. We said, hello, and he asked me to take a photograph of him against the watery background. His name was Hasham. I hadn’t met him before. He told me he was Indian by birth but had lived in Northern England almost all his life. We stood together for a long while drinking in the scenery. Before we set off again, Hash asked if he could ride with us. We said yes, of course. Then we stayed together till the end of the rally.

A few kilometres further on, we stopped again by a huge temple standing in the middle of a field. And again by another distant river. Other riders stopped too or passed on by. Some stood up on their pegs to catch the view, or waved as they passed. Apart from the occasional Enduro and a few people on foot going to and from the fields, we were alone on this silent country road.

It was while we were standing, wathcing the waters of the river slowly sliding by that we had our first encountner with Ali and the camera to which she was firmly attached. Ali was a kind of ‘unofficial photographer’ to the rally. She hitched pillion rides from the Enduros all along the route, stopping off here and there to photograph the scenery or the bikes and riders. She had got herself dropped off by the river so that she could capture the view and was now waiting by the side of the road to pick up another lift. She rode with me for a while, snapping away as we went.

Hash and Larry

Hash and Larry

Twenty kilometres further on and the world changed once more. We were back on broader and busier roads but still among wild country. We stopped for a break and a drink at a wayside stall. Several Enduros were already hanging about drinking tea when we arrived. Larry, Hash and I dismounted, stretched our legs and discretely wriggled our bums. I was already beginning to experience the first symptoms of Monkey Butt, that well-known by-product of riding a Royal Enfield Motorcycle. Monkey Butt isn’t pain as such, just an unpleasant creeping numbness and the uncomfortable impression that your gluteus muscles had taken on the qualities of shrink wrap. “Built like a Gun” had been the motto of the British Enfield Motorcycle company. “Hard as a Bullet” might have been just as appropriate. It was a tough little bike with an even tougher saddle (for which, read ‘plank’).

I didn’t want tea myself. Indian tea is brewed in a large container with milk and an industrial quantity of sugar already thrown in. For someone with a biochemistry like mine, Indian tea approaches the condition of a poisonous substance. I wandered about taking in a few details and feeling a little vague from this morning’s ridiculously early getting-up time and several hours of magnificent but highly focussed riding. There wasn’t much to see. Two painfully thin dogs were pawing over a large pile of vegetable leftovers by the side of the road. Several women were walking up and down attempting to sell garlands of flowers to parked motorists and Enduros. Larry and Hash were deep in conversation. I needed to take a leak. (Now stay with me on this one. It’s educational! If you are walking, camping, cycling or motorcycling in any foreign country, you need to know what the acceptable public behaviour is in the bowel and bladder departments.)

Behind the stalls was a steep, tree-covered slope which dropped away to the village in the valley below. Rising up the slope was a dirt track - an oddly busy little track since, at this end it ended in almost nothing (apparently): just the stalls, the road and miles of rough hill country as far as the eye could see. I found my way down among squat trees and bushes for about twenty yards, hoped no-one was coming and began to battle with all those bloody zips and press studs.

I was already half way through the business when I realised I was not alone. Two women with the same idea, were squatting in the bushes nearby. Now, I have no personal modesty in matters of this kind; I could quite happily dispense with most of the social rules around toilet behaviour, but it doesn’t do to go offending other people’s taboos and sensitivities for no good reason; so I carefully found a tree on the other side of the path and turned my back on the two women. This act of minimal politeness was met by great waves of giggling from the other side of the path. One of the women was Indian the other was an Enduro, but they were both helplessly amused at my behaviour. The giggling was followed by a mini-lecture from the Enduro on the ‘spiritual freedom’ of having a pee in the 21st century. (

). Does anyone else understand this? For all I knew she might have been like one of the ‘caravan club ladies’ I work with who would have forced her husband to drive over two counties to find a proper loo rather than pee in the bushes. Ah well!

The matter of appropriate toilet behaviour was settled for me soon after when an Amercian Enduro asked an Indian chap the whereabouts of the nearest toilet (or whatever euphemism an American would use for a public lavvy). The man looked puzzled for a moment and then, remembering he was in the presence of an alien being, flung wide his arms and replied in classical vein: “India, one very big toilet, sir.” Well, that was a relief! From that point on it was possible to get on with essential business, without unnecessary expeditions or gymnastics.

About nine kilometres further on we saw the junction we were looking for. We turned off the main road and immediately joined a throng of Enduros, Crew members, and an ambulance driver, all of whom were hanging about, taking a break before starting off on the next, very different leg of the journey. Nearby were two signs, one announcing the nearby presence of the Kaiga Power Generating Station ('No Entry') and another pointing in our direction saying simply, ‘Bare.’

This was it! This was the unmade road I had been looking forward to. The Enduro India Crew had really done a lot of work on it. As we stood about, glancing up at the steep, folded hillsides all around u, Simon told the tale of how they had found it. His story went like this. In their search for some really great rough-biking roads they had begun by ransacking the shelves of Indian Libraries. But large-scale road maps of India just do not exist and local roads are known only to local people. When they found no decent maps of any kind on library shelves, the Crew turned their attention to the universities. They contacted a number of academic departments until they found a professor of geography, who had some old Ordnance Survey Maps of India from the time of the British Raj. (One thing the British have always been very good at is making maps. It is practically an obsession. The old OS maps are some of the best ever made, anywhere).

With the help of the OS map, The Crew identified the old Bare Road as a possible candidate for what they wanted and went to take a look. It was perfect, they decided, but needed a lot of work to make it passable for bikes. When they first found it, it was thoroughly overgrown. To get through on that first occasion they had to lift their Enfields over fallen trees and hack their way through the undergrowth. They got permission from the Karnataka government to open it up. It took them several years to clear it and even now they still have to take chainsaws up there every year just before the ride.

It was briefly perfect, Simon said. Then things started to go wrong. As soon as the road had been cleared, the Karnataka government started to ‘improve’ it. At first The Crew tried to explain this was not what they intended, but then realised that the government was seizing the opportunity to turn it into an escape route for the nearby Kaiga nuclear power station in case of an accident. Not so reassuring! Simon laughed. “Nothing happens that fast in India and so far the improvements haven’t progressed very far. The road is still brilliant,” he said.

Riders began to power up. The ambulance driver got into his cab. I lingered for a moment to take a few more pics, then set off behind him. Big mistake!

For some several hundred yards the Bare Road ran along the open hillside, still reasonably surfaced. Then suddenly, as can happen even on conventional Indian roads, the tarmac ran out and was replaced by sandy soil and bare rock. The ‘road’ turned a corner and plunged into the dense hillside forest. The surface dust must have been a foot deep in places. This was totally unexpected. Yikes! I had some hairy moments in those first few minutes. I thought I was going to lose the bike at least a dozen times, and twice I was sure I was going plunge off the road and down the side of the hill into the trees. If anyone had seen my face during that time, it would have been worth a photograph. My pupils must have dilated with shock because everything suddenly went very bright. But again, the Enfield coped very well. It was far more planted and handled better than I could ever have hoped for. I didn’t go down; I didn’t go over the edge, and that began to give me a little confidence. Gradually, I recovered from the mire of panic that was drowning out my thoughts, and got control of my riding. I convinced myself that I was going to survive.

However, the track was not the kind of place to find yourself following close behind an ambulance, especially on a bike. I was riding into a total sandstorm thrown up by the vehicle's back wheels. I could see no more than a couple of inches in front of me. And I couldn’t overtake because the ambulance was occupying the whole width of the track. In any case, every physical and mental function I had available was still concentrating on staying upright. Overtaking would have required more presence of mind than I could muster just at that moment.

But I had to do something. If this goes on much longer, I thought, I’m going to finish the day travelling in this bloody ambulance as a passenger. The image of riding through all that dust for the next god-knows-how-many kilometres grew in my mind and became so vivid that suddenly something inside gave way.

I am usually fairly even tempered but I was now seriously p1ssed off. And there is nothing like being p1ssed off to help you get over inhibitions or anxieties. So the moment I saw the tiniest gap opening up between the ambulance and the edge of the road, I didn't think, I just did the Indian thing – I jammed my thumb onto the bike’s horn and dived into it. I had just enough space to stay on the road with my bar end occasionally scraping against the side of the vehicle.

Stupid? Foolhardy? I don’t know. But I got past the ambulance with a delicious sense of aggressive determination churning in my belly. And as I passed the cab, I was whooping at the top of my lungs. The driver was laughing and gave me a thumbs up. As soon as I was clear of the big lumbering four-wheeled thing behind me I rolled on the throttle and tore up the track. I’d passed some kind of psychological barrier, one that was to give me a different perspective on riding for the rest of the trip - and beyond. (Now, back in England, I realise my riding has taken a quantum leap forward and is freer and more confident than it ever was in the past. One moment. That's all it took.)

A sense of present reality did eventually penetrate my skull again and I slowed a little to make my way up the long track, past little waterfalls and over fording streams. The track markedly improved the higher it got, until it turned back to solid earth, strewn about with small stones. Down in the valley to my left, dumped bizarrely in the middle of the jungle, was the Kaiga nuclear power station. I got an occasional glimpse of it, but paid it little attention. The amount of energy that was being generated down there among the trees was nothing to the sheer adrenalin charge that was zinging away up here on the Bare Road.

I was still experiencing the tail-end of that adrenalin rush and feeling that I could tackle anything when suddenly up ahead the road surface changed again. When Simon had said that, “they were improving this road,” he didn’t mean it in a general sort of way, I suddenly realised; he meant literally that ‘road engineering works are taking place at this very moment as we speak.’ Overlying the dusty red soil, up ahead, were several hundred yards of newly laid hardcore: sharp hunks of broken stone up to four inches across, not yet pounded down and not yet settled into some sort of stability.

“You’ve got to be kidding!!!”

But no, this was for real. Adrenalin is amazing stuff. The manic glee of that first rush was now all but gone but the determination remained. I put my head down and hoped for the best. I just couldn’t have imagined myself doing that three days ago.

‘Looseish arms, even throttle, let the bike pick its way…’ I remembered the advice a friend had given me back home, and I did as I’d been advised. Once again I was surprised at how well the Enfield coped. Great bike! In the end it was me that funked out. About two-thirds of the way across, I fixated on the guys who were watching from far side of the stones (including Simon, who was laughing his b******s off) and suddenly I got all self-conscious. Immediately, I stalled the bike and then couldn’t kick it back into life. It took me about a minute to get the engine going again. And as I stood there, thumping away at the kick start, I was watching some of the other guys going by. The most successful ones, I noticed, kept the throttle open and took it all at a fair speed. OK, if that’s the way to do it… Well, it seemed to work. I cleared the hardcore and rode onto the bridge at its far end.

Among those watching from near the bridge was Ali. She was crouched down to one side of the track with her camera, recording everything that happened. We learned about Ali over the next few days. Wherever there was a likelihood of some dramatic event; wherever there was a nasty corner or a sheet of loose gravel; anywhere where there was likely to be a tumble, there you’d find Ali with her camera, waiting patiently for the inevitable. When she wasn’t sitting it out on dodgy corners, she’d be riding on the back of some guy’s Enfield, facing the wrong way, with her long legs and arms at all angles, and her camera snapping. If there was a good camera shot to be had, you could rely on Ali to be there to find it.

Ali (extreme left), always on the alert for a juicy spill

Ali (extreme left), always on the alert for a juicy spill

Hash made it over the stones a little behind me and Larry followed. The bridge offered a pleasantly level bit of surface to rest on. The three of us spent about quarter-of-an-hour hanging around on it, watching the guys behind tackling the hard core, yelling them on and eventually developing something of Simon and Ali’s relish for disaster.

Here's me still covered in dust from the ride up to the bridge

Here's me still covered in dust from the ride up to the bridge

Beyond the bridge, the sandy track continued uphill for a couple of hundred yards till suddenly we came across not only more hard core but an extensive audience of Indian road workers who had clearly not been so entertained in years. My heart sank. I’d done my bit, I thought. I was feeling proud of myself for having made it across the first stretch without dropping the bike. Surely, I had a right to feel smug for a couple of hours without having to undergo a second test.

But having managed it once, the second attempt was easier. And apart from one moment when I got too close to the edge of the road (i.e. the edge of a small cliff) I managed it all quite easily and without my heart relocating itself in my mouth. Hash and I got across, but Larry unfortunately dropped the bike and went down. He’d been uncertain about the trip from the start and was so keen to avoid an incident of any kind, I was afraid this might dent his confidence, but he seemed OK. After a moment, he picked himself up and waved us on. I was beginning to realise that riding over this kind of surface demands attack and not caution if you are going to carry it off well. I was learning a hell of a lot in a short space of time.

Once over the brow of the hill, some three or four kilometres further on, the track turned into a metalled road and once more began to descend steeply through the wooded hillsides. And what a road! A real twister! These were bends to die for! Cliffs or steep banks rose up on the left now, and dropped away to the right. It was a brilliant sun-shiney afternoon. Beams of sunlight were slanting down through the thinly leaved trees and spreading warm dapples all across the road. It was then that I knew I was going to remember today as one of the great days of my life.

My road riding was taking a quantum leap forward too. I was beginning for the first time to understand the practical sense of making late turn-ins. I was also beginning to realise that late turn-ins are not just technically ‘correct’ from a racing point of view but amazing fun as well.

The road rolled on down the mountainside, seemingly for ever. And that was fine by me because I never wanted it to stop. When it did level out eventually onto the valley floor I was sooooo sad. In the village we took another lemonade break at yet another wayside kiosk and had yet another crazy encounter with the local kids. Scores of adults gathered nearby too, laughing and smiling, come to take a curious look at the Westerners in all their strange gear.

But the best of the day wasn't finished. Beyond the village there was more good riding. These roads were just magic. I was starting to string the bends together well now. But there were many blind corners and you had to be hyper-vigilant, ready to swerve to right or left at a moment’s notice. There was very little oncoming traffic but what there was couldn't be seen until it was almost on top of you, and it might be on either side of the road. The tarmac surface was poor, and you had to keep a look out for the worst potholes. but I was beginning to realise that the Enfield on its Dunlop tyres didn’t seem to mind them too much. The road gradually widened out until, eventually, we turned onto a massive National Highway - the widest I saw in all my time in India. And once on this road we were back avoiding the trucks again in their dozens.

We were still high in the mountains and this new highway was full of sharp turns and one or two hairpins. I was enjoying myself so much that I'd run on ahead of Larry and Hash and was riding more or less alone. Then something extraordinary happened. As I rolled around a corner at a good lean, a short woman with two very dark, very wiry children dashed out of the dense trees and down a bank to my left. The two children placed themselves on the sandy verge with their arms held wide while the woman went into a semi-crouch between them and cast some small object across the road directly in front of me. She was ululating as she did so in a high-pitched voice, and as she let go of the object she made some strange vatic gesture in my direction.

It all happened very quickly. Their movements were energetic and ritualised. I thought of stopping but I had a large lorry closely following directly on my tail. The incident puzzled me for ages. I saw nothing like it again while I was in India. I couldn’t decide whether it was some kind of ritualised tribal magic, or just someone in a bad temper, or… What? I asked a couple of Indian guys about it at Om Beach where we were staying that night but neither of them were able to a make anything of it. The woman, her movements and gestures, left such a dramatic impression upon me that I have dreamed about them several times since.

On the valley floor the National Highway straightened out for a long run, inviting you to open the throttle and blatt your way down the highway. The Bullet’s 60 km per hour felt like 150 on my Triumph. Riding interest was supplied by the unpredictable antics of trucks and busses coming the other way

John looking mean and moody after a day's hard riding, and some trucks, of course...

John looking mean and moody after a day's hard riding, and some trucks, of course...

We pulled over among a muddle of stationary trucks, Enduros and busses. On one side of the road, just beyond another road barrier, there was a mobile kiosk and tea stand, on the other there was a petrol station, a good place to fuel up for tomorrow. We saw plenty of road barriers in the course of the journey. Some of them were state broundaries, some were entries into game reserves and some just seemed to be there for the hell of it. I had a soft drink then queued up at the pumps for fuel. The National Highway had been a blast. Despite the trucks it wasn't all that busy. It was wide and easy riding, but it had the potential to be lethal. The trucks were a real menace.

...And more trucks...

...And more trucks...

While queuing for the pumps we heard rumour of an accident. A young Enduro called Gavin (the youngest rider in the rally), had been bowling along when a truck pulled out for an overtake only yards in front of him. (I swear, these guys just do not look.) That left him with two choices, he could hit the truck or he could run off the road onto the sandy verge. He ran off the road at about 60km/hr, hit a rock, burst his front tyre and rolled off the bike. He said afterwards that he had stood up straight away but then collapsed again immediately as the shock hit him.

...and yet more trucks

...and yet more trucks

Fortunately, the ambulance was only a couple of minutes behind and he got rapid attention. He came back to the hotel in a neck brace and with a lot of nasty cuts to his face and a split lip which had to be glued together. He was fairly new to motorcycling. I heard that the bike was a write-off, but Gavin was up and riding again on a new machine in a couple of days. [Edit, 2 July 07: Just heard on the grapevine that Gavin's bike wasn't a write off. The mecahnics worked on it overnight and got it back on the road ready for him to ride the following day. Bloody good for them, and for Gavin!] You have to hand it to the The EnduroIndia Crew. They may not have been good at communicating with us over small things, but when it came to matters of importance, they didn't hang about.

Hash and I

Hash and I

At the pumps I met James. He too had had a bad time. Somewhere, back on the twisties, he’d taken a right-hand bend a little too fast (by his own admission) and ran into a patch of gravel. He’d slid off to the left and made several forward rolls into a ditch. He came out of it with some nasty looking abrasions all the way down his left hand side. He said that his bike was unharmed (sturdy little buggers, these Enfields) and he insisted on riding the rest of the way to the hotel. But when I spoke to him at the pumps he was in a lot of pain and just wanted to get to Om Beach as soon as he could for the evening surgery.

A quiet way to make a living

A quiet way to make a living

After filling up we turned onto another wide road, even busier than the last, which took us through some big rolling hill country a few kilometres inland from the coast. It swung lazily back and forth. Coming round one corner, we could see that something was going on down in the dip below. A number of Enduros had pulled up onto a lay-by and were getting out their cameras. Then something colourful caught my eye. A local festival! That’s a familiar sight in India. Indians love to have festivals.

'Festival of Youth'

'Festival of Youth'

This was a ‘Festival of Youth,’ we were told. Well, why not? If you've got it, celebrate it! As we arrived, about eighty peope in colourful outfits were standing by the roadside. They were gathered about a couple wearing elaborate theatrical costumes and fierce painted masks. By the time I had got out my camera the festival party had begun to process up a path among the roadside trees towards an ornate temple at the top of the hill. They a vivid splash of colour among the foliage. I was half-tempted to ask if I could come and watch, but I was also tired and wanting to get to the hotel. Larry and Hash wanted to get back too. In the end we rode on, but I made a mental note to come back to India again - soon - and give myself time to explore things like this.

A mile further on, at another lay-by, there was very different kind of celebration: it was a bike meet of some kind. There were some big laid-back looking cruisers and custom bikes among those on display. I think that was the only time I ever saw big cruiser-type bikes in India.

Salt pans in the distance

Salt pans in the distance

The road we were following eventually swooped down off the hillside towards the coastal levels and to a wide, watery plain stretching right to a vague horizon. I thought at first that we were looking at more paddy fields for growing rice, but as we got closer they took on more of the appearance of salt pans. Whatever they were, they were huge.

We reached our destination, Om Beach Resort at Gokarna, at about six o’clock. I found my chalet and then went down to reception to pick up my luggage. Our bags and cases were strewn about all over the courtyard. Several eagle-eyed young porters were hanging around and spotted the moment I had identified my baggage, then got to it first. There was the usual quarrel among them about who was going to carry what (one of them, a skinny lad, picked up the largest case, informing me proudly that he was attempting to build some muscle! “Strong man!” he said indicating a straining biceps.)

There were five of us sleeping in one chalet: two guys were lodged in one room, three of us in another. I was sharing with a couple tonight, Phil and Emma, both northerners. So, of course I got the single mattress on the floor. But that was cool! I can sleep most places. The bathroom was a huge tiled space, almost as big as my house back in England. It was certainly big enough for a rugby team. But the main thing was, it had a great shower.

Salt pans near the coast at Gokarna

Salt pans near the coast at Gokarna

After sorting myself out, I went down to the open-air snack counter and bar to see if I could find Hash or Larry. Instead, I bumped into the twins, Peter and David. Peter (or was it David?) told me a little about himself, then introduced me to his identical twin brother, David (or was it Peter?), and then to another David, Peter’s brother-in-law. (Confused yet? I was. I never learned to tell David and Peter securely apart.) We spent an hour or so, all of us, talking together on the lawn, under a glorious starlit sky, eating Bhajis and drinking Kingfisher lager. What else! (Despite the great diversity of India, there seems to be a mono-beer culture.) We talked about many things, some funny and some serious, until, as the evening wore on, the conversation turned slowly to personal matters, and I eventually told them all about Di.

The snack-bar team at Om Beach resort at Gokarna. Wonderful onion bhajis!

The snack-bar team at Om Beach resort at Gokarna. Wonderful onion bhajis!

Di, my wife, died last year from Motor Neurone Disease. (There’s a lot about Di and her illness and death on my regular blog so I won’t repeat any of the details here except to say that I’m still missing her badly and before she got ill we had planned to do this trip together.) I talked about her for… it seemed ages. The twins spoke personally too about some sad moments in their own recent lives. Then David (or was it Peter) told me something that made my heart pound.

We were looking up at the sky, when suddenly he pointed out the constellation of Orion. For David and his daughter, just as for Di and I, Orion possessed a very special meaning. It was in some sense a symbol of their love for one another as it was for us. Orion, the Hunter, is always visible in England (when it is not overcast by cloud). In winter time he stalks low on the Eastern Hills; but in the summer he rises high, and dominates the whole sky. He makes a powerful presence. Somehow he seems more distinct than other constellations.

Di and I often used to walk together in the evening, over the common land beyond the little market town where we lived, or up onto Windmill Hill. It was always a time of closeness for us. And we always used to look out for Orion and find him in the sky. His enduring presence was reassuring somehow, especially in troubled times, and we both loved his mythology and his name.

Orion is also visible from many places in the world, and for David and his daughter it was a symbol of family togetherness. Often separated by thousands of miles, each would look up into the night sky and know that Orion, so still in the heavens and yet so full of dynamic energy, would be shining quietly over the other wherever they might be.

It was a lovely warm evening. Despite all my best intentions, I finished it off, like the last, in a mild and pleasant alcoholic fug. I’ve never really made up my mind whether I like or dislike what alcohol does to me, but tonight it made me feel good. And I was very tired. Eventually, I keeled over on the hotel lawn with all the chattering Enduros around me and slept there peaceably for at least an hour under the stars with Orion prominent among them.

Our chalet with one of the guys I was sharing with

Our chalet with one of the guys I was sharing with

I can just remember getting myself up and stumbling over the now almost-deserted lawn back to my room. I slipped into bed. Phil and Emma were just settling down too. We negotiated about the ceiling fan, which cooled down the air beautifully but was blowing up my single sheet cover into a tempest of activity.

The room was tall and pleasant with a huge glass panel in the centre of the ceiling. The panel was broken in two and one half was missing. Through the gap, among the attic shadows, I could just make out the shapes of huge roof beams. They reminded me of an old barn I used to play in as a child, when the farmer was out of the way. I slept heavily that night, right through until the alarm call at seven o'clock the next morning. I slept peaceably, too, unaware that several of my room-mates had lain awake through half the night wondering about the large animal that was thumping around in the attic above us.

Thank you so much for showing us.

Thank you so much for showing us.