Cornish holiday

OK, today's blog is strictly for those who like the long ones. I'll warn you that there's not much about bikes in it. My excuse is that I did ride the Daytona down to Cornwall for this holiday and also rode it around while I was there. But mostly I visited the Eden project and pottered round the coast on foot. For hardened bikers who have no interest in this namby-pamby stuff, the bike-related bits are in blue. But there are also some pictures for those as like 'em wiv a bit'uv colour.

This is Part One of the blog. (Got exhausted). I'll put up part two (mostly pictures) in a couple of days.

...............................................................................................

Memories of the West Country

A breeze was blowing off the sea sufficient to raise a few small waves on the lower reaches of the river. The air was warmish, but still quite fresh. Two close friends, Rohan and Ashley were backpacking with me along the south-west peninsular coastal path. We were having a glorious time. Our immediate plan that evening was to make it to The Gribben by nightfall where we hoped to find somewhere to camp. The Gribben is a headland, east of St Austell on the south Cornish coast.

Throughout the morning and afternoon we had walked steadily westwards over the clifftops, dipping frequently down into steep-sided valleys. These were cut through the coastal hills by Cornish rivers as they headed towards the Atlantic. By the time the sun had begun sinking towards the horizon we had passed through the village of Polruan and were sitting aboard the little passenger ferry which was ploughing slowly across the deep-water estuary of the river Fowey.

Hundreds of sailing craft bobbed about on the waves. The wind had set their rigging beating rapidly against their masts, filling the estuary with a metallic clacking sound. That sound evokes a whole world of boats and sailing for me. I always associate it with this part of the world with its many little ports and harbours. Further up the estuary a large merchant vessel was filling its hold with china clay dug out of the open-cast mines near St Austell.

Loading china clay

Loading china clay

The ferry boat docked efficiently at the small town on the western shore and we stumbled off. This is Fowey, a lovely place, very old and very attractive. It's a small merchant port and fishing town which takes not just its name but also its livelihood from the river. It's still home to rivermen, dockers and sailors as well as those who cater to the tourist industry. Like the river, it’s mood is relaxed and slow.

Fowey from the river

Fowey from the river

From Fowey, we still had several miles to walk before we could put up the tents and settle in for the night, but we were tired and felt no urge to hurry on. The evening was coming on with reassuring slowness. We loitered on the quay for ten minute, then ten minutes more, then half an hour. We talked and leaned on the railings, drinking from our canteens and filling our stomachs with sugary biscuits. Near the quay was a small square fronted by the King of Prussia pub. A group of teenagers were hanging out by the pub entrance, arguing with each other. Their voices were raucous with angst and frustration.

The coastal road out of Fowey rises slowly up towards the castle on the estuary headland. As we walked in its direction, we looked out over a scene of natural beauty, modified and humanised by centuries of making and doing, and glowing softly now in the evening light. On one side, the coast road was fronted by elegant houses, all painted in pastel shades and adorned with porticoed entrances. On the other, shaggy-looking cliffs dropped steeply down to the water’s edge. Across the estuary, rising up the hillsides to the woods above, the fishing village of Polruan, prinked and twinkled in the rosy light. It was a gorgeous autumnal evening.

On the way up to the castle, we passed above the ruins of an old stone-built blockhouse built into the cliffs by medieval masons. Its twin stood out stolidly below a dark bluff on the other side of the estuary. For centuries, machinery within the two buildings had defended the river and its towns by raising a heavy, half-mile-long chain across the waters whenever the threat of pirates or an invading navy was immanent.

Ruins of blockhouse

Ruins of blockhouse

We rounded the headland, descended to the beach at Readymoney Cove and then headed for the steep steps which took us up into the Readymoney Hills beyond. A flock of pigeons were foraging among the glades. Rohan (wait for it!) had been studying hypnotherapy, and decided that he wanted to try to put one of them into a trance. No comment is required, I think! After all, have you ever tried to catch a pigeon's eye, let alone hypnotise it?. After ten minutes and several pigeons later, the last remaining bird cocked its head questioningly, and strutted away. I guess it is good to have an experimental turn of mind.

Daymarker on Gribben Head (with jersey cow). The daymarker

Daymarker on Gribben Head (with jersey cow). The daymarker

(the big red and white stripey thing) was set up on the headland

in the nineteenth century as a warning to shipping - 'cos there is an

awful lot of Atlantic out there just over the hill.

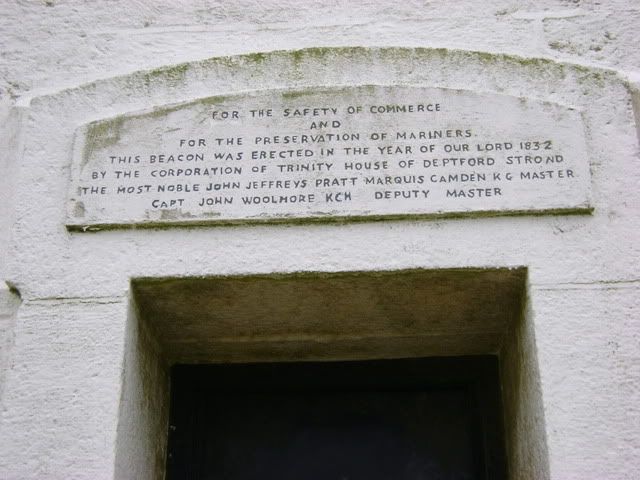

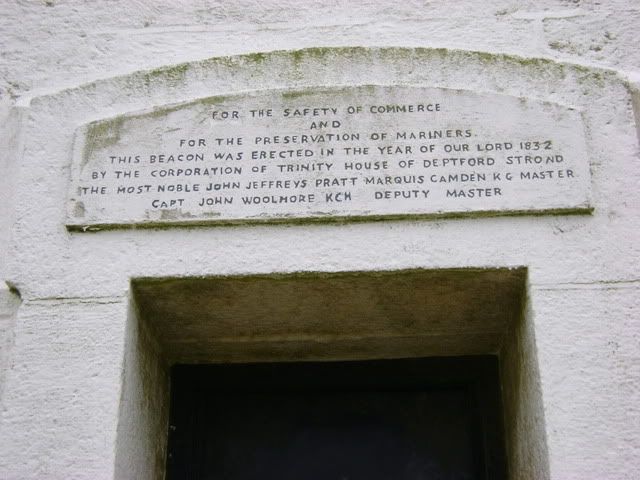

Trinity House dedication on the daymarker (Trinity House

Trinity House dedication on the daymarker (Trinity House

was a company set up by the family of Robert Louis Stevenson -

author of Treasure Island, etc. Until recently it was responsible

for building and maintaining the lighthouses and beacons around

the shores of GB).

By the time we got our first good view of the "daymarker", the tall, red-and-white striped beacon on the top of Gribben Head, the sun had gone down and the evening light was beginning to fade to grey. By this time, we were exhausted and our backs and shoulders were aching with the effort of carrying heavy packs all day.

By nighfall on the cliffs, there is no-one else around. I've always thought of this as the best time of the day. As the beaches and clifftops empty of people, the land takes on a wild and lonely appearance. In the failing light you can imagine yourself one of the last human beings left on earth. The sea the land and the sky cease to be a mere backdrop to human activity and begin to take on independent and moody personalities of their own.

We pitched our tents and set up camp quickly in the long grass not far from the marker. We cooked a meal of rice, chick peas and frozen veg (now unfrozen and soggy after several hours in our rucksacks.) After that, we sat about on the tussocky ground for an hour or two talking. Then we watched the sky. It was brilliantly clear and set with thousands of stars.

Finally, we rinsed the plates, arranged our gear and crawled into our tents. As we settled down to sleep, little did we know that what we were in for was a very eventful night…

…………………………………………………………………………………….

As I walked over Gribben Head two weeks ago, the memory of that evening and the events that followed came back to me in extraordinary, almost photographic, detail – which is astonishing, since they took place nearly thirty years ago.

At the time of that original walk, Di and I had only just met, and parting with each other for the duration of the holiday had been exquisitely painful. But the walk was a boy's-only adventure and an annual ritual of the most solemn kind. In those days it seemed to us as though nerve, bone and muscle had been specifically designed for no other reason than to walk the Cornish coastal path. For ten years, our long walk was the most important and defining event of our lives.

Rohan, Ashley and I had hitch-hiked the four hundred miles down to the Cornish coast. That was part of the ritual too. Hitchinking was still common at that time. Today, drivers no longer give lifts, and the sight of someone standing at a roundabout with a thumb stuck questioningly in the air is now a rarity. This year, when I trekked down to Cornwall, I rode the Daytona, and travelled alone.

Sorting through the lumber in my attic last September I came across a pair of old walking boots - the same pair I'd worn back then. They had been resoled and restiched several times before being abandoned in favour of a more comfortable, more modern pair in the 1990s, but they were still in good condition and I'd never had the heart to throw them away. On a whim I decided to take them with me.

Stepping out along the coastal path in the same pair of heavy-duty boots that I had worn thirty years previously was a strange and nostalgic experience. Those long walking holidays back in the 1970s had provided me with some of the happiest and most contented moments in my entire life: the cliffs, the woods, the hills, the pubs and the amusement arcades in the seaside towns had mingled together in my mind to create one blissfully glowing memory.

Three weeks ago though, the experience was different. As I retraced my footsteps up to Gribben Head, I was recalling the smallest of individual details: where I had slipped and nearly fallen on a muddy slope; where we had halted for a drink; and where I had stopped to take a photograph and to wonder whether I had enough film left in the camera before we got to St Austell. I remembered not just the events but also how I felt: tired and achey, a bit light-headed from having eaten too much sugar, deeply happy but just a little anxious about whether we would find a good site for the tents. Even fragments of the conversations that had passed between us came back to me.

Rohan, my oldest and for many years my closest friend, was in my thoughts. In our twenties and thirties we had walked hundreds, probably thousands of miles together, backpacking, sleeping out in tents or under the stars. In those years we made camp wherever the night fell on us. We had pitched our tents at various times on bare moorland heights, on scrubby heaths and on swampy river banks. I remember evenings fighting off mosquitos, or watching the sides of the tent collapsing inwardly under a torrential downpour. I remember dancing naked on the cliffs one night, roaring like a madman, as a huge thunderstorm blazed and rumbled overhead.

We'd slept out on sandy beaches and pebbly beaches. We'd slept in ploughed fields, in woods, and on mountain tops. We'd camped in broad Lakeland valleys and in narrow Cornish defiles. Often, we'd slept at the foot of cliffs or high up on cliff ledges overlooking the sea. On cold or particularly wet nights, we slept in abandoned barns, caves, or old mine workings. We tried to scare each other by telling ghost stories while camped among the remains of ancient megaliths, long barrows, and iron-age forts. One night we camped in a swannery. On another, when we were just too tired to go any further, we crashed out on a municipal rubbish tip.

Unfortunately, the world always woke before we did (Rohan is even worse at getting up than I am) and our camping arrangements were not always welcome to others. We were sometimes shouted at or threatened by irate parking attendants, red-faced farmers and local jobsworths. Once, on an early morning walk over Hengisbury Head I met the park warden. Standing on a ridge overlooking our empty tents, I tut tutted with him sympathetically and bemoaned the irresposibility of youngsters who ignored the 'no camping' signs and put up their tents on National Trust land.

When we were benighted in town, we nipped over fences to camp on school playing fields or racecourses, in public parks, on road embankments, on private lawns and even, just very, very occasionally on campsites - but only when they were out of season and there was no-one around. We were very particular; we had standards to maintain! Sometimes we never pitched tent at all, but walked all night long in the moonlight, just talking, laughing, boasting and horsing around.

Rohan is now a city boy living on the outer edges of London. He is no longer a roamer. He no longer fantasises himself as this or that character from the Lord of the Rings, and he doesn’t now try to hypnotise pigeons (though I’m not entirely sure about that). He has acquired two children on the way and now wears worry lines in his forehead. I don’t see him very often, but when I do, I note that he is still a stubborn bastrd and likes to scare the dodo out of me whenever he can. I haven't managed to get him onto the back of the Daytona yet, but when I do...

The world still seems as beautiful a place as it was in the days when we used to walk together, but it is a lot more familiar now and some of the intensity and excitement has drained out of it. My thoughts are more prosaic than they once were. I have fewer illusions, I guess, which is probably just another way of saying that I have now reclassified my illusions as 'reality'. There are compensations that come with 'maturity', of course, but I still regret the loss of that early sense of boundless possibility. Despite everything, I still need to feel the hills around me, to be out in natural world and to walk and ride through it. That is as essential to health and wellbeing as breathing.

Five weeks ago, I desperately needed to get away from home and work and all the self-defeating thoughts that go along with those things. I considered various options, but in the end, headed off to Cornwall. There was a good chance it would still be reasonably warm down there in the West Country. I took time off work for the trip, and then looked forward to a fortnight out in the open air. But as with most things, it didn't quite go as I had planned. (Not that I had planned it in much detail. Planning and detail are not exactly my thing.)

In my general kind of way, I was intending to have a moody time, walking the coastal path and sleeping rough on a couple of beaches I know where the big Atlantic rollers break on the sea rocks all night long and their booming echoes off the cliffs behind.

Instead, the first ten days of my sixteen-day break were spent at home nursing carousel flu – the kind that goes merrily round and round. I had three separate bouts of fever in that time. On day eleven I did manage to rouse myself sufficiently from my torpor, and, snuffling into my lid, rode the 400 miles down to Cornwall. But I was still feeling pretty rotten – much too rotten to sleep out as planned. So, just before I left home, I booked myself into a bikers' B&B outside St Austell and left my camping gear in the cupboard. Instead of doing a lot of solo soul-searching among the rocks and caves and contemplating what I was going to do with the rest of my life, I spent my few remaining days on and off the bike, pottering around the coast, visiting a friend and seeing a few of the things on my must-do list.

I took the familar route on the way down: After negotiating the A1(M); M25: M3, I sidled off onto the always interesting A303; and then onto the dull but business-like A30. Finally, the A390 took me down to Parr, a village lying a few miles outside St Austell, but far enough away from the town to be out of sight of the slag heaps from its gigantic open-cast mine works.

Since I didn’t leave home before 3.00 in the afternoon, I spent most of the outward journey riding in the dark. I might just as well have taken the M4/M5 and got there a lot more quickly. (Ach! No. Not really! Ignore me. Fallout from the flu has left me feeling mouldy and resentful. I actually enjoyed that ride, even though I didn’t get to see much of the scenery.)

It was a cool evening and despite putting on as many layers as you would find in a filo pastry, I was pretty chilly by the time I got to Parr. But it didn’t matter. The ride was easy: the motorways and the A30 are good roads on which to square off your tyres. The A303 is more interesting and has some great scenery (when you can see it) but is not very twisty. The A390 which took me the last stretch down to Parr was a dark, winding road and at last forced me to put on a proper motorcycling head.

Cornwall is a great place if you are into being moody. It is a wild and stormy part of the island - dark golden brown like muscovado sugar: at least it is in my imagination - golden brown is the colour of its magnificent sea cliffs. It's is a long finger-like peninsular which juts out into the Atlantic, a world all of its own, separated from the rest of Great Britain by the River Tamar. It is a place of myth and legend: King Arthur and the round table, mermaids and piskies, ghosts and standing stones. It once upheld romantic traditions of seafaring, smuggling and piracy. Although constitutionally a part of England, the county has its own very particular identity. Locals tend to think of themselves as ‘Cornish’ first, and refer to the rest of us, none too sweetly, as ‘The English’. English is the local language here now, but the native Cornish, closely related to Welsh and Breton only died out in the middle of the 20th century.

Cornwall has its own flag: a vertical white cross on a black background. Nobody has a flag quite as sinister-looking as the Cornish. You will see it flying everywhere. Cornwall also has its own distinctive climate: the southernmost parts round Roseland and The Lizard are semi-tropical. They used to be hotter than the rest of the UK, but global warming is changing all that.

Eeny-meeny-miney-mo. I decided on the Daytona, for the ride down. It is not as comfortable for long journeys as the SV1000 but it is a lot less vibey. Although the SV’s vibrations are more irritating than unpleasant, that distinction becomes merely academic when you live with them for some six or seven hours at a stretch.

It’s a pity because in most ways the SV is a perfect long-distance sports tourer. It eats up the miles comfortably. On long stretches of motorway or major A roads, it's a great companion. Its twin engine is very characterful. And it packs a real punch. Like an intelligent sheepdog, it stays in constant communication with you, letting you know what it needs are and asking you what you want. The Daytona, on the other hand, almost melts away from under you and seems to guess your intentions even before you know them yourself. Sitting astride the Daytona sometimes feels like riding on air.

Roads in the south of England always seem to be infested with road-works these days, and I don’t ever recall there being quite as many as there are at present. Everywhere you go, you come across long lines of traffic cones, gangs of workers, and the inevitable speed restrictions. In the increasingly sophisticated surveillance culture of the UK, we now have to deal with the monstrous 'average speed cameras’. These are placed every mile or so beside the roadworks. They are hooked up to computers which recognise your registration number and calculate your average speed as you travel between them. Average more than the set limit and there is a letter for you in the post. Fortunately, they are front facing so they cannot identify bikes which have their registration plates on the back. The rest of the traffic, however, has to play ball and is not particularly obliging in the narrow lanes. (Not that I would recommend overtaking in those circumstances, of course!)

As I wearily slowed up at yet another set of signs indicating roadworks ahead, it occured to me to wonder why you see so many more of them in the UK than on the continent. There are a number of reasons I guess: the highways agency in the UK notoriously uses inferior materials to build the roads and consequently has to repair the surface more frequently; the winters are colder in the UK than southern Europe, and that tends to break up the tarmac more quickly; the traffic is so dense here that road surfaces get a terrific hammering day after day and just can't take such a lot of punishment; and finally the government is forever adding extra lanes to roads to cope with the increasing traffic.

Whatever causes them, roadworks are a bloody nuisance.

Riding in the dark on a cold night is a strange business, especially on unfamiliar country roads: it's a lonely and, at the same time, comforting experience. Your horizons narrow. Consciousness closes in on you and thoughts echo more loudly inside your head. Night thoughts are very different from those of the day, more intimate, more focused, sometimes surprising. In the dark, I start to develop an unexpected sense of kinship with other road users. (During daylight hours, motorists are just a nuisance.  )

)

My normal habit on a long ride is to plough on as hard and fast as I can. On this occasion though, I reined in and took it easy. I stopped off at service stations three times on the way down. This was partly to refuel the bike and partly to refuel my demanding stomach. But it was also partly just to look after myself. I was still in the grip of post-flu syndrome and just not feeling quite like king of the road. At each stop, I felt in no hurry to get going again.

Finding the B&B when I finally got to Parr turned out to be a lot easier than I imagined. As soon as I hit town I pulled up by a dropped kerb to check out the address and the map. The map was unclear about road names, but once I stopped poring over it for information and started to look around me, I discovered that I had stopped directly outside my destination! How lucky is that?

I'd found this particular B&B in the BMF guide to Cornwall, which meant that it provided good secure garaging for the bike. The couple who owned it were friendly and helpful. Despite the late hour they provided me with a cold meal, and I was soon in bed.

The next day I left the bike where it was in the garage, pulled on some walking boots, slung on a day pack and set out on foot for the gardens of Eden. Eden lies a mile or so from the sea and about six miles from St Austell. What was once one of the town’s semi-abandoned china clay pits, an ugly white gash in the undulating landscape, is now something close to a miracle of abundance and thriving human activity.

The road I found to take me to Eden was no more than a narrow farm track that cut its way steeply up over the coastal hill ridge before dropping down to the sea. Up hill and down dale it ran between tall banks and hedges, through a remote farming country of scruffy fields and tiny, isolated hamlets. Nothing about this landscape could be said to be beautiful. It is hard and utilitarian, heavy with an almost tangible sense of the slow, difficult labour that goes into its cultivation. The ploughland has a dense and claggy bulk that deadened all sound. And when I turned off the road onto a muddy track, and got my first glimpse of Eden, I was more than a little disappointed. I had built up this moment in my imagination: it was going to be something exceptional. What I saw was unusual, but nothing more. It made me think, initially of some carelessly managed industrial complex sitting down in a dip. It wasn’t until I got a little closer to it and saw the whole panorama of domes and gardens that I began to appreciate the extraordinary scale of the place, and when I did, I just couldn’t stop staring.

As early in the day as it was and as late in the season, the crowds were already pouring down the access roads from the car and coach parks when I arrived. Even though I knew it was a big attraction, I had no idea it was going to be this busy. Since Eden opened some nine years ago, it has had a phenomenal popular success, completely overwhelming its creators’ wildest expectations. And why shouldn’t it? It’s an extraordinary and spectacular place.

Here are some pics.

First sight of Eden's biomes

First sight of Eden's biomes

The whole site is full of giant sculptures

The whole site is full of giant sculptures

Inside the small tropical biome

Inside the small tropical biome

River flowing inside the large tropical biome

River flowing inside the large tropical biome

Tropical biome

Tropical biome

Tropical biome

Tropical biome

Ladder leading to viewing platform in the roof of the large tropical biome.

Ladder leading to viewing platform in the roof of the large tropical biome.

To get some sense of scale, check out the circle of hexagons in the roof of the biome. The small rectangular structure below them and a little to their right is a viewing platform reached by the ladder in the photo above.

To get some sense of scale, check out the circle of hexagons in the roof of the biome. The small rectangular structure below them and a little to their right is a viewing platform reached by the ladder in the photo above.

Mediterranean biome

Mediterranean biome

Sculpture celebrating the 'river of oil' flowing from the olive growing regions of the Med. The whole of Eden is dedicated to explaining how we use the natural world to meet our needs.

Sculpture celebrating the 'river of oil' flowing from the olive growing regions of the Med. The whole of Eden is dedicated to explaining how we use the natural world to meet our needs.

Sculpture of Dionysus and the Maenads showing the amgibuous advantages of the vine.

Sculpture of Dionysus and the Maenads showing the amgibuous advantages of the vine.

The huge domed ‘biomes’ are, in effect, the world’s largest conservatories, though that description really doesn’t do them justice. They are spectacular in construction and design. One group of domes contain a hot, steaming tropical jungle and the other, a cool, dry Mediterranean landscape of vinyards and olive groves. The outdoor ‘biome’ reproduces the flora of temperate regions from around the world. What impressed me most was how upbeat the place was, not just a draw for plant lovers, but a day out for anyone.

The domes and gardens are full of sculptures, exhibitions, and interactive events of all kinds. On the day that I arrived, there was a Halloween happening going on in one of the buildings. Hundreds of people were already skating on a decent-sized indoor ice rink. The whole place is lavishly decorated with plant life and gives an overwhelming sense of the earth’s abundance. The biomes and the exhibitions are fascinating in themselves. Close by is 'The Core' a huge new building full of some of the most imaginative and fun educational exhibits I have seen. It is constructed, the brochures tell me, using a double spiral design frequently found in nature. At its centre is a special room constructed to house a huge stone sculpture called 'the seed.' The project claims it is the largest stone sculpture ever attempted since the time of the ancient Egyptians. Let's say, it is big!

The biggest draw though, is the tropical biome. It reproduces three jungle environments, one from south America, one from eastern Africa and one from Indonesia.

Stunning sclupture of a horse made from driftwood. It's amazing how it captures the sensitivity of the living animal even though it is made out of dead material.

Stunning sclupture of a horse made from driftwood. It's amazing how it captures the sensitivity of the living animal even though it is made out of dead material.

Leaving Eden was difficulty, partly because I really didn’t want to go, and partly because the signage on the way out was appalling. It gave me precise pointers on how to get to Mevagissy or Mousehole, further on down the Cornish Coast, or to Exeter, back up there in borin’ ole ‘England’ but it didn’t tell me how to get to St Austell, just six miles away. I was planning to walk down into town to get an evening meal and then catch a bus back to Parr.

After walking a mile or so in what seemed increasingly to be the wrong direction, I turned around, grumbling to myself, and started back. On the way I hailed some passers-by and asked for directions. They were a young couple. They said they were going towards St Austell and offered me a lift. They were environmentalists (unsurprisingly in a place like this): one worked for the Centre for Alternative Technology at Llwyngwern, near Machynlleth, in Wales, the other for a conservation project in central London. Amazingly, we discovered we had friends in common.

I ate at a pub in St Austell. The food was served by a thoughtful but humourless barmaid. The place was almost empty. Most of the time I was there, the barmaid devoted her efforts to expertly manage three local winos, who sat up at the bar, one dressed in a sailor’s heavy serge coat and peaked hat. All three were deep in their cups, cursing roundly, and making slurred accusations that the others were unable to hold their liquor. It was hilarious!

I caught the bus home, asking the driver as I got on to give me a shout when we were close to Parr, as I didn’t know the town and might miss it in the dark. Being a country bus it took the back roads, twisting and turning in and out of the villages. I had no idea where we were, so I asked again when I thought we must be getting close.

I don’t know what it was about this bloke. It turned out that the bus route only touched the outskirts of Parr and then carried on somewhere else. I had no idea we had even been there. Normally if you outride your fare, a bus driver will let you know pretty sharpish - but not this one. It was only when we had left behind all signs of habitation and travelled half a mile up an extremely dark, narrow, muddy and dismal farm track that I realised that we weren’t now anywhere near where I wanted to be. I walked up the front of the bus and asked again. When I found out that we were way out on the other side of the town I demanded to be let off. He gave some lame excuse for not telling me that I didn’t fully understand and suggested I stay on the bus - he would be coming back this way in an hour! Now way!

As the bus drew away, I found myself standing in pitch blackness at the side of a deserted and muddy country lane. I got out the map and a torch. It was cloudy. There was no moon, no street lamps and the sky was like ink. On both sides, the lane was hemmed in with tall hedges. Hmmmm! I reckoned it was six miles back to the B&B. As soon as my eyes had adjusted to the light, I turned off the torch and got walking. My spirits were high. I love walking in the dark. The only thing that was truly lacking was an isolated country pub.

All in all, by the time I got to the B&B, I must have walked about fourteen miles that day.

..................................................................................................

Until then, here's some more pics of Eden - just can't get over this place.