Wolf in India

-

blues2cruise

- Moderator

- Posts: 10182

- Joined: Fri Apr 22, 2005 4:28 pm

- Sex: Female

- Years Riding: 16

- My Motorcycle: 2000 Yamaha V-Star 1100

- Location: Vancouver, British Columbia

- noodlenoggin

- Legendary 300

- Posts: 415

- Joined: Mon Jul 17, 2006 2:08 am

- Sex: Male

- My Motorcycle: 1995 Ford Thunderbird =-(

- Location: Lithia, FL

- sv-wolf

- Site Supporter - Platinum

- Posts: 2278

- Joined: Sat Dec 13, 2003 2:06 am

- Real Name: Richard

- Sex: Male

- Years Riding: 12

- My Motorcycle: Honda Fireblade, 2004: Suzuki DR650, 201

- Location: Hertfordshire, UK

22nd Feb

Day 1 of the Rally

Start: Old Anchor Hotel, Kavellosim (Goa)

Finish: Beach Huts on Palolem Beach (Goa).

Distance: 184 km on the clock, 20km as the crow flies.

“Today is designed to break us all in gently. This rally stage sees us tackle a beautiful and demanding stretch of the Western Ghat mountain range on our way to Palolem, our first night’s destination. Palolem is one of India’s most beautiful beach resorts. During the riding day you will encounter mountains every bit as spectacular as the Himalayas, just with lots and lots of forest and no snow peaks, due to the reduced altitude. Today is short in length to give us all a chance to build confidence. It is a stunning and remote ride. Get ready for very rough accommodation and a breathtaking location tonight – the rally has begun.”

From The EnduroIndia Roadbook 2007

I woke up feeling pretty damn excited this morning. I was just aching to get my teeth into an adventure. It had already started in my head - and in the rest of me as well. I could feel the energy fizzing in my muscles. I could feel it in my bones. ‘India! Indiaaahhh!’ There was, however, just one little issue – how was I to get out of bed? You may laugh, but this is a serious ergonomic problem that I face every morning of my life.

If I were at home right now, the dominant part of my brain would be reasoning thus: The Adventure is already going on in my head. My head is happily lying on my pillow. Ergo, there is no conceivable reason why I should get out of bed. (It’s amazing how practically useful a dry-as-dust degree in Philosophy can be sometimes.) But I wasn’t at home, and the real world was yelling at me from beyond the curtains to get up and join the party.

With a kind of overmastering impulse that came out of nowhere, I swung out of bed. I stood upright, rubbing my eyes and blinking at the world as I imagine the first man must have blinked at the moment of his first awakening into consciousness. I even got through those critical first two minutes of the morning without bumping into anything or collapsing back down onto the mattress. Some serious business was going down.

Pip was already bustling around in the bathroom. I could hear the sleepless bulk of Brian next door shifting himself out of bed like a lead weight. There was already a clattering on the stairs and on the paths outside our chalet as other Enduros were making their way across to the outdoor breakfast tables. Within moments I was fully awake and packing, washing, dressing and hauling my luggage down to the hotel reception where it would be picked up by the trucks. It would soon be on its way to tomorrow night’s destination – Om Beach. For some reason it wasn’t going to where we would sleep tonight - a collection of huts on Palolem beach, “very rough accommodation” according to the Roadbook. We were advised to take our sleeping bags with us on the bike.

Sambhar for breakfast again! As I said, I like this curried food but…

It wasn’t fair! Everyone else was wolfing down platefuls of scrambled egg and big rounds of bread. But not me! I was doing what all nineteenth-century British colonial administrators in India feared. I was ‘going native!’ I couldn’t eat the scrambled eggs because the hotel chefs had cooked them with milk, and I am seriously allergic to dairy products. So I had no choice. Curried breakfast it was, to be followed – no doubt about it – by curried lunch and curried tea, and curried dinner too. On the bright side, they were serving some sausages! Yummy! Sambhar and chicken sausages! There’s not a lot of pork to be had in India, so most sausages here are filled with chicken meat. Different, but tasty!

Where was Larry? Larry and I had met up in the hotel reception yesterday. Larry was probably a little older than me. He was looking for someone who roade at his pace. He said he was a slow rider. I’m not so slow, I told him, but I would probably end up at the back of the pack because I intended to spend a lot of time taking photographs and talking to people. He said fine, and we agreed to ride together. The arrangement suited me well. I didn’t want to ride with a big group because it would be more difficult to stop when I wanted.

Larry

The EnduroIndia team had insisted that we ride in groups of at least two in case of an accident. That was partly for obvious reasons, but partly also because there had to be someone on hand to prevent the ever-helpful locals from taking charge - moving someone when they ought not to be moved, or whisking them away to some unknown hospital, where no-body knew where they were. And there were other issues. Put it this way: getting vaccinated against Hepatitis C is often recommended if you are travelling to India. It’s not a big risk - unless you are whisked off to an Indian hospital.

EnduroIndia had two ambulances and a medical crew who constantly rode up and down the route. There was never a medic more than a few minutes away. In case of an accident, we were advised, it was best to give them a call on your mobile and let Doc, or Kip or Andrew or one of the nurses or paramedics deal with the situation and make the medical decisions.

Larry is a genial but reserved American (I’ve not met many of those.) He told me he was from Chicago originally, but had built up a business in London and had lived there with his wife for the last 20 years. He sounded very American to me and he had a very unBritish sense of humour, but as I got to know him over the two weeks of the Enduro it became clear that his adopted culture had rubbed off on him to some extent and he had acquired something of a European perspective on the world.

He almost hadn't come out to India. After booking his place with Simon (the guy who owns and runs EnduroIndia) he had suddenly developed some serious reservations about the whole trip. It took all of Simon’s powers of persuasion (and believe me, they are considerable) to get him out here. Larry is relatively new to bikes, but has ridden a trike back home in London for some while. (Riding a trike in London sounds like my idea of a nightmare – but Larry said he loved it.) The main thing though was that he was out here. And being here he had no intention of spoiling his trip by having and accident. Accidents are common on the rally, so he took to riding very carefully.

This first, proper day’s riding was going to take us on a long ‘U’ shaped journey directly up into the mountains through the towns of Panaji, Old Goa, and Ponda, and then back down to the coastal plain via Cancona. That’s a total riding distance of 184 km - except for those that got lost, of course. (And we were assured by Simon that many of us would get lost – Simon is endlessly reassuring.) But Palolem beach, our destination, is only 20 km down the coast from Kavallosim our starting point – a reminder that the best journeys are taken for the journey’s sake and are not just a way of putting distance between us and our beginnings.

At least that’s the way I think about it. We were a mixed bunch of riders, composed of everything from full-time racing professionals down to complete novices. At the one extreme there were the total bike junkies, those that might have been on the moon for all they cared. All they were interested in was the ride (and the beer, of course!). If India had looked to them exactly like the Nurburgring, they would have been completely satisfied. Up there with the junkies were the speed freaks and the goal-oriented achievers. These guys would be soaking in the showers at Palolem before the rest were even half-way home.

At the other extreme were The Travellers. You could tell The Travellers because they were festooned with cameras. They carried guide books in their tank bags and had a good line in conversation. Their often dreamy eyes lacked the sportsbike rider’s slightly crazed and focussed look. Riding with The Travellers would be most of the novices (though some of the completely new guys rode extremely well) and the genuinely easy-going souls who couldn’t work out what the hurry was all about.

In temperament, I would place myself somewhere in the middle, or more strictly, I’m a bit of both. The paradox of my life (and I'm still trying to sort this out) is that I have a nervous system that is so sparky it seems to have its own amphetamines supply, but a disposition that is never really in much of a hurry to do anything. On a bike, I never know whether to crack open the throttle or just saunter along and take in the view.

India magnified my perennial state of indecision. What should I focus on: the ride or on the scenery? Both were magnificent. But, sure as eggs, I couldn’t do both at once. So, I alternated every day between the two. In practice, though, I usually ended up at the back. (It’s just in my nature, I can’t help it) And I mean - right at the back! with the EnduroIndia ‘Back Marker’ drumming his fingers on his tank while I got off the bike to take one more photograph or chat to one more group of people, or just to get soulful for a while up in the mountains. Even Larry sometimes got just a little bit frustrated with me, I think.

I mopped up the last of the sambhar with the idli, gulped it down and made my way over to the field where the bikes had been rearranged into a giant arc. It was a dramatic sight. Every bike had a newly blessed garland of flowers hanging from the bars and around the headlight. (A Hindu holy man had come and done the honours with great ceremony the previous evening.)

The first day meet opposite the hotel

I started the bike a lot easier today. I could fire it up in about a minute now, and Sonny had more time to see to other business. I was confident that I’d got the left-right, down-up business with the gears sorted out in my mind, so my nerves were a lot less tight than it had been the day before. (I was to have the occasional high-revving, gear-crunching and sharp-braking moment almost to the end of the rally, but mostly I’d got the measure of the bike by this second riding day.)

Ben again, looking thoughtful (total squid who surprised everyone with his riding)

The extroverts among us were already beginning to reveal themselves. Toby and David’s bikes were already rather more decorated than the rest. And it wasn’t difficult to spot Kevin, Justin, Colombo and several others from their crazy riding gear. Ali was there with her camera. So were the other ‘official’ photographers. The video crews were lumbering around with all their equipment; the mechanics were roving about, eagle-eyed in their orange tabards; the team were swanning around in their yellow ones; the ambulances and medics were waiting near the entrance. And the whole shebang was just about ready to roll.

The EnduroIndia camera crews got everywhere. Every year the organisation makes a film of the event and shows

it in a London cinema. They also produce a DVD.

Once we were away from Kavallosim and the hotel, we emerged quickly onto a busy main road. The column of bikes began at once to string itself out as the front runners forged ahead. For the first 60 kilometres or so, the route lay along fairly major roads and gave us a more developed taste of Indian driving skills, like the easy habit of making blind double overtakes (one vehicle overtaking another, which was in turn overtaking a third on a blind corner.)

No prizes for guessing where this guy is from

The land soon began to rise steadily but not steeply. With greater confidence today and on roads like these, my modest desire to stay alive was now being replaced by some rather more natural biker instincts: like the instinct to ‘make progress’ and to overtake. It was a great feeling, bowling along these roads with so many other bikers out here in this amazing country. And of course, it was another lovely day. But so were they all - all lovely days.

At thirty-two kilometres we made our first major river crossing. The rivers here are wide and magnificent. At the lower levels the palm forests sweep down right to their banks. At higher altitudes deciduous forests blanket them on either side. I stopped on the far side of the bridge for a break and to take a few photographs. There aren’t that many broad, powerful rivers like this in the UK. (I remember, at the age of seventeen, being miffed when an American friend referred to the Frome, one of the major rivers of southern England, as a ‘creek’.)

The first river crossing

But I’d stopped also for another reason. My new helmet was a white off-roader. I’d bought it specially for the rally because I reckoned that it would reflect the sun and allow air to circulate well. It was doing those jobs OK, but right now it was beginning to give me a sharp pain in the side of my head. It had felt fine when I bought it and when I’d worn it for half-an-hour or so at home, but not now. I’ve got a very round (Arai) head and the new lid was clearly the wrong shape. Damn! Not the best of times to find out. There wouldn’t be much chance of buying a new lid before the end of the rally. All I could do was to thumb the lining material and try to widen its inner profile slightly. It worked – a bit. But I had to keep doing it right throughout the trip, and I never got an entirely pain-free ride after that. Once I’d worked on the inside of the helmet though, the pain was mild and most of the time I was able to ignore it. When I couldn’t, it was a matter of shifting the helmet around so that the pressure wasn’t concentrated on one spot.

While we were standing by the side of the road with a lot of other Enduros one of the mechanics happened by. The mechanics always stopped when a group of us were taking a break and did a visual check on the bikes. One of them noticed that my front tyre was slightly flat - just very slightly. I hadn’t realised myself. I gave it a kick. How could he tell? It looked fine to me. I rode the bike a couple of hundred yards down the road to where their van was parked and one of the mechanics checked it. Sure enough it was a little low and he put a few extra PSI in it with a foot pump. “Keep an eye on it,” he warned.”

Well that would give me something to think about. I now had a tight lid and a slow puncture.

Taking a break on the way into Old Goa

Eighteen kilometres further on and we were running among some very heavy traffic alongside another wide river. This was the approach to the town of Old Goa. Old Goa still had a very European feel about it. The large Cathedral and various other major buildings were clearly of Portuguese origin. The town had wide streets with well-manicured verges and was exceptionally clean for India.

Larry amusing three schoolkids. When they asked him where he was going, he had to admit

that he didn't know

On the outskirts of Ponda, the next town, we stopped to discuss the Route Plan which was suggesting we should carry straight on past a junction and through Ponda, itself. Despite the confidence of the instruction the road layout proved it to be a complete nonsense: ‘straight ahead’ was not going to go anywhere near Ponda at all. Various other groups of Enduros had pulled over to ponder the same problem. The Route Plan was generally very good but not always. A proper map would have been useful at this point, but when I asked the EnduroIndia team a little later why they hadn’t given us one, I was told that maps which included the minor roads just did not exist. I tried to think of a map of Hertfordshire without the B roads on it, and I felt a certain insecurity coming over me. Arriving here from a world of information overload the idea of a vast country like India that was mostly unmapped was fascinating, and also reassuring. I sometimes think the less we know about things the less we can "fudge" them up.

India: graceful and filthy, orderly and chaotic; these contrasts were everywhere

I tried asking a truck driver how to get to the next town. He was pulled up by the side of the road and relaxing in his cab. He didn’t speak English so we didn't get very far. Showing him the Route Plan and waving my arms about didn’t work either. But he eventually caught the word ‘Molem,’ the name of the next town, and he suddenly brightened. Once again I was taken aback by the depth of the Indian desire to be helpful: the look of relief and excitement on his face when he understood what I wanted was astonishing, and he took obvious pleasure in pointing out the way for me.

Molem-A dusty truck stop town

We’d been seeing trucks all day, compact-looking six or eight wheelers, carrying various loads, but often piled high with the red soil that seemed everywhere in this place. On the way into Molem we passed so many trucks going in both directions that they seemed like two continuous convoys.

Molem again - the trucks rumbled through continuously all the while we were there

Molem turned out to be a dusty truck-stop town in the middle of nowhere. It had a petrol station and some small kiosks selling food and drink. I needed to fill up with petrol and I wanted to get my front tyre pressure looked at again. It seemed OK, but I had begun to convince myself that maybe it wasn’t. For the last fifteen kilometres the road had been rough and heavily potholed. I hadn't noticed last time and it seemed likely from the meagre information provided by the Route Map that there wouldn't be another garage for miles. I queued up. As it turned out there was no air pump at the fuel station but it did mean that we got to hang around this amazing place for half-an-hour or so.

Larry bought a bunch of tiny bananas from a kiosk for 2 Rupees each (about 2p or 3 cents) and shared them out. I’ve never seen such tiny bananas. They were no more than two or three mouthfuls each. I guess they are probably harvested wild here. They are probably not commercially viable for transportation over long distances. But they were fine. We found them everywhere after that. They would form a good part of our diet while we were on the road from that time on. Fruit is sterile so long as the skins are still intact when you buy it, and here in India bananas are nutritious and plentiful.

Larry thoughtfully considering the mini-bananas in Molem

At Molem we turned off the main road and off the main truck routes as well. Three of four kilometres further on I saw my first elephant. It was chained up by the side of the road dozily pushing a scattering of hay about the floor. John and Julia had passed us while we were still in Molen and had ridden this way about twenty minutes earlier. Julia had asked to be given a ride on the elephant's back. She has sent me a disc of her photos. This is hers.

Julia's Elephant GP

After Molem came Colem, and after Colem came miles of deciduous forests and rolling hillsides, which got thicker and more beautiful as we rode deeper and deeper into the mountains. The narrowing roads were soon crowded on both sides by trees and shrubs and dense foliage of all kinds. We turned right by a sign announcing “road improvements” then made a quick left. And straight away we were rolling downhill and onto a road that was still waiting to be improved. It was no more than a rough track of loose soil, cut about with huge ruts and potholes. The change was completely unexpected. The Route Plan had given no warning of it. In a matter of a few yards the rules of the game had suddenly changed. It was a different landscape and a different biking experience.

The moment we hit the track, my body went straight into emergency mode. The easy-going ride was over. For the next few minutes I was too focused on the ruts and shifting soil, and too busy trying to stay upright, to notice immediately that my anxiety levels had suddenly risen exponentially. I’d never ridden on this kind of track before. Where it was dry the ground threw up clouds of dust, where it was wet there was a red oily slick.

It soon became apparent though, that the Enfield was perfectly at home on this kind of surface - more at home than I was, and more than I would have ever imagined any road bike could be. I began to relax a little. And then a little more. Suddenly I found it exhilarating. The Enfield was hilarious! It tackled this stuff without the slightest difficulty and it handled just beautifully! What a bike!

We turned under a bridge and found ourselves running parallel to a busy railway goods yard. There seemed to be a lot of raw material haulage around here though I couldn’t make out exactly what it was. More of the red clay, perhaps? They must need a hell of a lot of bricks in Goa. The route kept us turning off one narrow track onto another, each one narrower and more remote seeming than the last. And suddenly we were completely lost in the middle of rural India. The rough, and occasionally sodden, surface continued, though it wasn’t for another seven kilometres that our Route Plan made mention of the fact with a single, innocent-sounding instruction: “Continue along muddy track.”

There wan't anything else to do. Eventually we hit another junction. this time we turned onto a broader track, but one that was equally dusty rutted. And here we began to meet the trucks again. They came rolling down towards us in twos and threes – dozens of them – travelling at speed and flashing their headlights at us. In India when a vehicle flashes its headlights like that it means only one thing. It means: I’m coming through – GET OUT OF MY WAY! And that is what you have to do; you have to get out of the way, even if it means riding into the hedge - because they are not going to stop.

The trucks were everywhere along this stretch, bouncing along at lunatic speeds. And rarely on the right side of the track! (Was there a right side of the track?) Most were painted a vivid red and decorated from top to bottom with all sorts of graphics. They were a real hazard to life and limb. But already I began to notice a perverse kind of idea growing in my mind: dodging them was beginning to feel like a lot of fun.

Most of the trucks also had some sort of slogan painted on them in English or in Indian script. I recognized some of the English slogans from roadside signs. They were all very worthy and comtemporary. I was told later that there was a practical reason for this. In India, trucks have to pass a regular MOT test (I'm not sure what the American or Canadian equivalent is – here in GB, it’s a yearly legal examination of all vehicles over three years old to make sure that are still road worthy.) I was told that the government officials who conduct the MOT tests here in India were unlikely to pass a truck unless it was carrying one of the current government’s slogans somewhere about it. That is downright corruption, like the way the ruling party uses Dordoshan the state TV system. Corruption here runs right through the entire political and business system from the bottom to the very highest levels. Everybody know it, everybody makes loud, morally outraged comments about it, but everyone turns a blind eye, or milks the system.

Goan roads are dominated by trucks

Indian trucks, I was told before I came out here, rarely have rear lights of any kind. My two weeks experience in India allows me to reveal that this is not strictly true. Most of the trucks we saw did have very colourful lights - but they were usually painted on! This place is glorious!

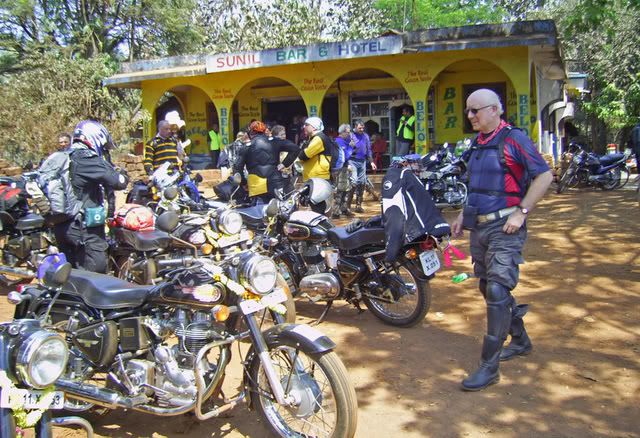

As we rode down the dusty track my spirits soared. Just one day into the rally and the Bullet was already beginning to seem like an old friend. I was already riding with so much more confidence that I had expected. Once the intial anxiety had worn off I was beginning to seriously enjoy this kind of riding. The day was beautiful. But that meant it wasalso thirsty work and I was beginning to get a bit fed up with the sun-heated water in my Camelback water carrier. So despite my good mood I was beginning to think that I needed to stop. Then, out of nowhere, we hit the village of Uguem and the Sunil Bar. Time to pull over. Others had had the same idea: there must have been a good twenty Enduros hanging out there already, all looking pretty floppy from the heat.

My sense of hygiene is, I would say, averagely male. I take sufficient care to prevent myself and others succumbing to a lot of unnecessary diseases, but on the whole, my awareness of being beset by germs is not particularly well developed. I don’t have nightmares about doing battle with armies of invading bacteria – like a friend of mine. That’s not me.

If you grow up in the countryside, you don’t get to fret about that kind of thing much. At least I didn’t. Nor did my folks. I passed many happy childhood hours rolling about in swampy pools, in rotting spinnys and in tic and lice-infested pastures. And I took particular pleasure in wading up and down smelly drainage ditches for hours at a time, exploring the mud at the bottom. We lived in a house which had pasture land on three sides of it. And when you are literally surrounded by domestic farm animals (not the most hygiene-conscious of creatures) every day of your life you can’t avoid being in contact with a fair number of wee critters. I was always falling into cow pats as child, I seem to remember, and survived perfectly well to tell the tale. I think that living among a thriving community of bacteria is useful for building up your immune system.

But… Hygiene in India is something else. We had been advised by the EnduroIndia medical crew not to eat salads, and most definitely not to eat meat unless we had seen it cooked in front of us. We were not to drink directly out of bottles unless we had a straw, nor to have ice in our drinks, nor to buy water unless we were sure the seal on the bottle was unbroken (otherwise its contents were likely to have come from the local river). And there were a dozen other rules as well. It all seemed to require a lot of care and attention. And I’m not very good at ‘care and attention’. But once you have spent a little time here, you begin to appreciate the need.

It is one of the paradoxes of this endlessly confusing country. Hinduism, the majority religion, has a very well developed sense of personal ‘purity’. People you see on the streets here are often extremely clean and well turned out, yet India itself is filthy. Take the Sunil Bar, for instance, where we had just stopped off for a break. It's in the photo below. The shop is on the left-hand side. It's open-fronted and sells a few meagre items of food and drink. It must have been doing a fair trade that morning as there were crates of empties piled all around it. I was getting fed up with sucking on sun-heated water from the Camelback and decided to go over and buy myself a bottle of lemonade.

The Sunil Bar and Hotel. (In India a hotel does not necessarily offer accommodation.)

I kept meeting the guys in black and yellow. They came to India from Cornwall as a group.

The inside of the shop was deep in shadow and felt pleasantly cool. To the right of the entrance stood a wobbly drinks dispenser. To the left was a short counter. Further inside, an ancient and very hacked-about wooden cabinet with a glass front stood at an angle to the wall. Apart from a couple of stools and boxes scattered about on the concrete floor, there was nothing else. The cabinet contained a few packets of biscuits, one or two other indeterminate food items and some bottles of fizzy drink.

It took a few moments for my eyes to adapt to the gloom, but as they did, I began to realize that the shop could not have been seriously cleaned out for at least twenty years. It was filthy. Though, to be fair, there was probably little point in trying to keep it clean with all the sand and dust that must have blown in every day off the road. India is a very dusty place, I'm beginning to realise. The glass in the cabinet had been smashed - long ago, but the look of it. But some large lethal-looking shards remained in place, projecting from the bottom of the frame. The surviving glass fragments were so dirty that it was difficult to see through them.

I asked for a lemonade – not without a certain hesitancy. One of the young guys in the shop came out to the front of the cabinet, reached in over the shards of glass, retrieved a bottle and handed it to me. The bottom of the bottle was caked with grime. But the lemonade tasted good - very sweet. Indians tend to have a very sweet tooth.

I didn’t have a straw so I had to put a few drops of concentrated grapefruit seed oil in the bottle. I wiped the top with some more. I use grapefruit seed oil a lot if I go abroad and am not sure of the drinking water. It is a very powerful anti-bacterial, anti-viral and anti-parasitical agent. After sharpening up my hygiene awareness at the Sunil Bar, I used it in all cold drinks (apart from alcoholic ones) while I was in India. This meant that for two weeks almost everything I drank tasted of citrus.

Because Westerners have bodies that are wholly undefended against most Indian bugs I had already decided to be particularly careful on this holiday. I didn't want to spoil my time here by coming down with Delhi Belly. And my immune system was more unprepared than most. Like many people who have a professional background in complementary healthcare I don’t have vaccinations when I go abroad. (I’ve read the reports; I know what is in them; I know what the side-effects are; I know what they do to the immune system and I know just how effective they often aren’t!) Instead, I had a trusted kit of non-pharmacological remedies with me. They are very effective, but I have to take them several times a day, which can be a bit difficult if you are out in India on a bike. Nevertheless, they served me well. In two weeks, while everyone else was coming down with queasy stomachs, I breezed through without the slightest problem.

Indian kids are great fun but must be a nightmare to their parents

Some kids from the village had got wind of the fact that there were Westerners about, so it wasn't long before we were surrounded by a collection of small hands and smiling faces. Indian kids are extremely friendly. When you first meet them they are often very polite and disciplined. But that is just on the surface. Underneath they are pretty wild and uninhibited. One of the Enduro team, Ross arrived and started to ‘hand out’ ballpoint pens. (That’s him in the photo - the guy with the pink beard.) He started off sucessfully enough by getting all the kids to line up. But the moment the pens appeared it was a free-for-all scramble. As soon as he pulled a handful of pens out his tank bag these charmingly courteous youngsters suddenly started to resemble a pack of crockadiles in a feeding frenzy. No holds were barred.

But their honesty is equally apparent. Put your hand in your bag to pull out some pens and you will find a dozen tiny hands in there with you scrabbling around to see what they can find. Pull out your hand and they will remove theirs also. It seems that there is no intention to steal. They wouldn't do that. Whenever something is on offer, they just want to get to it first before someone else does. This is competition red in tooth and claw. From everything I've read this competitiveness runs very deep in Indian culture. Offer a polite group of kids sweets, and their sudden determination not to be left out will leave you in a state of shock and bewilderment.

"Little ß@$τ@Þ₫s." And this guy is a teacher in real life.

Beyond the Sunil Bar the roads turned tarmac again and the remaining 40 kilometres up in the mountains were a wonderful, lazy ride among scrubby deciduous forest and acres of terraced hillsides. They were lovely roads and the Enfield ate them up. They wound and dipped, ran in and out, up and down, among the tightly folded hills. Then finally, we rolled back down the mountainsides, through the towns of Goadongrem and Cancona, back into palm-tree country and on towards the coast.

Terraced hillsides up in the Ghat Mountains. It's too high here for palm trees to flourish.

Somewhere along this last stretch I lost Larry. Suddenly, he wasn’t there with me any more. I rode back to find him, but he wasn't there. I raced forward but he wasn't there either. I told one of the team leaders whom I met, and he said he would look out for him but not to worry too much. There were plenty of riders behind me and up ahead. He would be able to hook up with someone. Eventually, and rather guiltily I gave up.

Wherever you stop in India, kids will gather round you and demand to be given pens. These kids lived in the

tentlike structures made out of of palm leaves in the background.

I attached myself instead to a group of Cornish riders I had met for the first time at the Sunil Bar. There were about six of them. They had come over to India together and rode as a group for the whole two weeks. They were unmistakable in their yellow and black, wasp-striped or chequered rugby shirts. I enjoyed travelling with them. They rode close to my top skill level and that kept me focussed and enjoying the bike. It was a great twisty ride (like so many) on narrow country roads that bucked up and down among the hills. Low shrubby trees were all that grew in the hedgerows at this altitude. The landscape was strangely reminiscent of Northrn England.

After sticking with them for about half-an-hour, though, the old feeling of wanting to slow down and look about a bit came over me again, so I lost them too. I finished the day on my own dawdling along and taking dozens of photographs. Despite the disapproval of The Team I began riding alone more and more as the days wore on.

For the last dozen or so kilometres the road made its way back towards the coast, dropping steeply downwards through a dramatic rocky landscape. The afternoon sun lit up the great bastions of rock on either side or threw them into shade. It was pure magic. It put me in a dreamy mood and the ride flowed. I could have gone on riding like that for ever. But nothing lasts. Eventually the road levelled out, and plunged back into the low-lying palm forest once again. I made my way by local roads, dusty and blown with sand, over to Palolem Beach and parked up my bike with the others among the beach huts. It was about four o’clock

I hadn’t realized how tired I was until I arrived and got off the bike. I hadn’t realized how hungry I was either.

Providentially, right opposite my hut among the palm trees, on the edge of the beach, was an open-air restaurant. I quickly dumped my gear in the hut, said hello to Brian, who was already there, and went over to inspect what the eatery had on offer. The evening meal provided by EnduroIndia wouldn't be for another four hours so I was in no mood to wait. I found the menu and ordered enough food to keep an elephant going for several weeks, and set about it with fine energy. It was great. With one notable exception, it was the best meal I had on the whole trip. Larry rolled up a short while later, safe and sound. It turned out that I had just run ahead of him. Whoops! Mustn't get carried away like that! Neither of us could work out why we weren't able to find each other again, though. I chatted with him in the restaurant for a bit and then went over to my hut for a shower.

Palolem Beach. My hut is on the right. The open-air restaurant is on the left. The space in the middle

is reserved for those that hire hubbly-bubblies in the evening.

The hut stood on stilts and was built from large panels of old plywood as far as I could see. The floor creaked alarmingly as I walked across it. It had two bedrooms and a 'bathroom'. The shower was a miracle of ingenuity. It consisted of a tap high on the ‘bathroom’ wall. The tap was fitted with a rose to spread the water. There was no plug hole to let the water out, just a gap between the slightly sloping floor and the wall. The sandy ground a couple of feet below was a sufficient soakaway. It wasn’t the hottest or most comfortable shower I have ever had but it was most welcome.

“Very rough accommodation” the EnduroIndia Roadbook had called our beach huts. ‘Rough’ is fine by me. Now that I'm in my middle-age, I’ve grudgingly come to appreciate the advantages of staying in hotels, but this sort of set-up is a lot more fun. I like to feel part of the landscape when I'm on holiday. Staying in a westernised hotel when you are abroad defeats the object, somehow. It puts up a barrier between you and the real world outside. I was glad I had brought my sleeping bag with me, though - Brian and I were apparently sharing a bed. You’ve got to hand it to the EnduroIndia team – no austerity was spared. The less it cost them to accommodate us, the more money they could give to the charities they sponsored and we had raised money for. That was fine by me, too. Behind the partition in the other half of the hut were Peter and David, identical twins. I got to know them a lot better a few days later but I never did learn to tell them apart.

Palolem beach is several miles long: a smooth arc of palm-fringed sand running down to the Arabian Gulf. Tucked away among the palms that fringed its entire length were thousands of beech huts, looking as though they had grown there among the trees. Facing the sea were dozens of beach restaurants, bars and kiosks selling holiday ware. The hut I was sharing was great. It faced directly onto the beach. But as there were no windows we couldn't enjoy of the view. Shame!

As everyone piled down onto the beach we got the news of the day's events. There had been some problems with dehydration. That was a real and constant threat. You have to remember to drink regularly in this heat - every fifteen minutes or so. Absolutely essential! We had all brought a Camelback-type water carriers (a compulsory part of the kit) but it was still easy to forget. The Camelback is a narrow backpack containing a water sack. You can wear this comfortably over your armour. It had a drinking tube which comes over your shoulder and clips onto the strap. With this kit you can drink regularly without having to stop or get off the bike. Only trouble is, out on the Indian roads, the tube gets very dusty and every first mouthful tastes just a bit yearrgh!

One group of riders reported some interesting encounters with livestock out on the roads today. They narrowly missed several large domestic mammals (including a cow - whoops!) and managed to kill a chicken. I didn't hear what the outcome was. Incidents like this can turn nasty in India, and the Crew had advised us, for small animals, just to ride on. For encounters with larger animals or people we needed to get the Organisers on the spot quickly. People involved in accidents have been literally lynched before now by angry mobs. 'Justice' here can be very local. I heard of one decking. A rider had skidded on a gravelly corner and gone down and his riding mate had run over his leg. There were no broken bones.

In previous years everyone had travelled over to a small offshore island in boats and eaten supper on the beach. It sounded idyllic. This year it didn't happen, though. The local boatmen, who used to take the Enduros out to the island in groups of twelve were suddenly saying they couldn't do it any more. There was a new regulation, they said, which forbade them from taking more than six in a boat. The general consensus among the Enduro Team was that this was bullshit. Their view was that the boatmen had seen an opportunity to double their income and had come up with this story. But it didn't do them any good. There was a change of plan. It would have taken much too long to ferry everyone out in small groups like this, so the team had hurriedly made other arrangements. We were going to eat at what was, by all accounts, the top Palolem eatery, only a couple of hundred yards down the beach from where we were staying.

The boat we never took to the island we never found

At about ten to eight, as the light was fading, I began to make my way over to the restaurant for supper. The atmosphere on the beach was amazing. I don't generally like tourist resorts much, and I'm not so keen on beaches, but I can see why people come here. It is just so laid back. I'd met up with Justin, one of the EnduroIndia Team, as I was walking, and started talking to him when a figure came running up behind and stopped us. It was Mary, still wearing her off-road armour. She and five others had just got in. She was laughing but exhausted. The group had taken a wrong turning near the goods yard, and had ended up totally lost in the middle of nowhere. At least half the team were still out trying to find them. No-one had ever got that lost before, Justin said, not on this stretch.

While Justin and Mary were laughing about the situation, a huge cloud of mosquitoes swept along the beach. I couldn’t see them in the evening twilight but I could feel them. There were so many that their wings felt like a single piece of soft cloth flapping about my face and neck. Southern Goa has a very low malaria risk, but it's not negligible and I had forgotten to dose myself up with Vit B1 that evening or use the insect repellent spray. I turned back to the hut to get them.

As it turned out they probably weren’t mosquitoes at all. Though what they were no-one was quite sure. Some said that they were flying ants, others that they were sand fleas. (I didn't think that sand fleas had a flying phase, but who knows?) Whatever they were, there were billions of them. They swarmed up the beach for about half an hour and then just as suddenly disappeared.

Palolem beach with its fringe of palms, beach huts and hot nightspots

The evening meal at the restaurant was good, but there was so much of it and so much choice! It was all put out in huge steel basins for us to serve ourselves. The basisn stood on a long line of tables that stretched for about twenty yards along the beach. There were fish and meat dishes, vegetarian dishes, dhals and curries, bhajis of all sorts, rice and poppadoms and naans and chapattis, sauces and soups and salads - and loads of other things I couldn’t identify then and can’t remember now. It was a feast. The highlight of the meal, though, was the fresh catch of king prawns. These were monsters. I’ve never seen prawns like them. They were so amazing I thought they merited a photograph all of their own.

King prawns laid out for our beach feast

We ate at a double arc of tables spread out along the beach, all lit with hundreds of candles. And above us was a brilliant starlit sky. Near the tables someone had started a fire of crackling driftwood. The warmth came drifting across to me. We talked, and ate and listened to the sound of the surf, while the warm coastal breeze blew over us and fluttered the candles. And for two hours I stuffed myself silly again (for a skinny guy, I have an enormous appetite) and downed serveral bottles of Kingfisher lager. I had promised myself no more alcohol on this trip, but on a night like this, who could resist. I couldn't. People moved around between helpings and courses and I started to get to know the group a little better.

We came from a wide variety of backgrounds, but the majority, I'd say were professionals or small businessmen. That was only to be expected I realised later. The EnduroIndia deal is that you pay £500 towards the cost of the rally and then you raise an additional £3,350 for charity. To raise that amount of money you have to have a lot of time and resources (or, in my case, a lot of generous and helpful friends), so I guess it would tend to attract people who have both.

At the table I talked to a bloke who was a Triumph dealer in the Midlands and to a reporter who worked for one of the broadsheet national newspapers. There were hoteliers and bank clerk among us, mechanics and entrepreneurs, and professionals of all sorts. I met up with Pip again. In the course of our conversation it emerged that Pip lived in Stevenage (where I work!). I also talked with David for the first time. David was one-half of the crazy, madcap David and Toby combo of which much more later. These two were seriously crazed, and very entertaining.

We got our head down early that night. Or at least I did, though there was a strong core of hard-drinking party animals among us who stayed up till the small hours of the morning. And they carried on the tradition right throughout the trip. Among them were most of the EnduroIndia Team. I am seriously impressed at how much alcohol these guys could put away and still ride a bike the following morning. They seemed to function well on it too. I’ve never had that kind of stamina.

As I dropped off to sleep I found myself wondering how Pip’s new room-mate was faring with that incredible ear-bashing. I slept well, but a lot of people didn’t. Palolem Beach is inhabited not only by hoards of partying humans but also by large packs of stray dogs who fight and bark all night long. I was vaguely aware of their howling as I dropped off. Brian woke up early next morning looking even blearier than ever.

Last edited by sv-wolf on Sun May 27, 2007 12:42 am, edited 3 times in total.

Hud

“Man has no right to kill his brother. It is no excuse that he does so in uniform: he only adds the infamy of servitude to the crime of murder.”

Percy Bysshe Shelley

SV-Wolf's Bike Blog

“Man has no right to kill his brother. It is no excuse that he does so in uniform: he only adds the infamy of servitude to the crime of murder.”

Percy Bysshe Shelley

SV-Wolf's Bike Blog

- sv-wolf

- Site Supporter - Platinum

- Posts: 2278

- Joined: Sat Dec 13, 2003 2:06 am

- Real Name: Richard

- Sex: Male

- Years Riding: 12

- My Motorcycle: Honda Fireblade, 2004: Suzuki DR650, 201

- Location: Hertfordshire, UK

Getting the next post up soon. In the meantime, here's some vids that other guys did on the trip this year. Try them out.

http://youtube.com/watch?v=02NdW85heY8

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AqrOpNHR2uM

http://www.uvouch.com/video-Enduro-India-2007-401718

http://youtube.com/watch?v=BWyoGD-ZD00& ... ed&search=

http://youtube.com/watch?v=Gon0VEOJWVs& ... ed&search=

http://youtube.com/watch?v=Gon0VEOJWVs& ... ed&search=

http://youtube.com/watch?v=fLc4KB5EZgk& ... ed&search=

http://youtube.com/watch?v=Tc9rK65yK8c& ... ed&search=

http://youtube.com/watch?v=h-sO4gcIgLE& ... ed&search=

http://youtube.com/watch?v=yfQl1wqqxq0& ... ed&search=

http://youtube.com/watch?v=DH28nR7-JTY& ... ed&search=

http://youtube.com/watch?v=02NdW85heY8

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AqrOpNHR2uM

http://www.uvouch.com/video-Enduro-India-2007-401718

http://youtube.com/watch?v=BWyoGD-ZD00& ... ed&search=

http://youtube.com/watch?v=Gon0VEOJWVs& ... ed&search=

http://youtube.com/watch?v=Gon0VEOJWVs& ... ed&search=

http://youtube.com/watch?v=fLc4KB5EZgk& ... ed&search=

http://youtube.com/watch?v=Tc9rK65yK8c& ... ed&search=

http://youtube.com/watch?v=h-sO4gcIgLE& ... ed&search=

http://youtube.com/watch?v=yfQl1wqqxq0& ... ed&search=

http://youtube.com/watch?v=DH28nR7-JTY& ... ed&search=

Last edited by sv-wolf on Tue May 22, 2007 8:59 pm, edited 3 times in total.

Hud

“Man has no right to kill his brother. It is no excuse that he does so in uniform: he only adds the infamy of servitude to the crime of murder.”

Percy Bysshe Shelley

SV-Wolf's Bike Blog

“Man has no right to kill his brother. It is no excuse that he does so in uniform: he only adds the infamy of servitude to the crime of murder.”

Percy Bysshe Shelley

SV-Wolf's Bike Blog

- NightNurse

- Legendary 300

- Posts: 353

- Joined: Sun Apr 01, 2007 12:46 pm

- sv-wolf

- Site Supporter - Platinum

- Posts: 2278

- Joined: Sat Dec 13, 2003 2:06 am

- Real Name: Richard

- Sex: Male

- Years Riding: 12

- My Motorcycle: Honda Fireblade, 2004: Suzuki DR650, 201

- Location: Hertfordshire, UK

22nd Feb

Day 2 of the Rally

Start: Beach Huts on Palolem Beach (Goa)

Finish: Om Beach at Gokarna

Distance: 210 km.

“The second day is longer and more demanding but feels no harder due to the fact you are becoming more confident on your bike and the forest trails and mountain passes are becoming less daunting. Today’s ride is quite simply mind-blowing as we wind our way on and off road all the way over the mountains and back to our night’s stop point at a truly secret cove, looking out to the Arabian see. Tonight the accommodation is packed tight and hot.”

From The EnduroIndia Roadbook 2007

I said goodbye to my hut (I’m a sentimental soul), turned my back on the lazy life of Palolem Beach and headed off into the palm forest to find ‘Beast’ (that’s ‘Beast’ as in, ‘Beauty and the Beast’) - my bike, my Royal Enfield Bullet and began to think about the day ahead.

I was looking forward to today's ride. This was going to be the first big ‘off-roading’ day of the rally – and the first time I had done any ‘off-roading’ of any kind. The idea of riding forest tracks in India sounded to me like heaven, one big adventure wrapped up in another. I have to admit that there was a nervous tremor in my belly as I walked out towards the bikes that morning. But like all other feelings and thoughts it was being swamped out by a flood of excitement.

‘Off-roading’ is what everyone was calling it but in fact, we were going to be riding on 'roads' all day today. It's just that, like everything else in this amazing country, the definition of a ‘road’ is very broad. It is applied equally to a National Highway and to the strip of semi-passable ground we would be taking through the hillside forests near Bare (pronounced Bar-ray).

Once, long ago, this ribbon of sandy soil had been a proper road, with a proper surface to it, but no-one had travelled it, except on foot, since the time of the British Raj – not until the EnduroIndia Crew discovered it and got permission to open it up again. Simon included it in the route for the first time last year. It had taken The Crew four years to get it into a rideable state. And even after all their work, it is still no more than a rough track.

I had no idea how well I was going to manage to ride on this sort of surface - I'm the guy who gets nervous riding over his mate's gravel drive. But I reckoned I’d soon find out. I was up for a challenge, and off-roading sounded like fun. Many years ago I discovered an important principle: if I wanted to do something badly enough, there was no point thinking about it. I just had to get out there and stand on the starting line. Once I had got that far, I was unlikely to turn back. And doing it that way, I enjoyed the experience all the more for not having a head full of pre-conceptions about it. I'm cautious (and lazy) by nature and if I hadn't learned that bit of wisdom early on, I'd have led a much duller life.

The way the Enfield had coped with the dusty lane the previous day had given an extra boost to my confidence and I was looking forward to something meatier. I wanted to have a few emotional highs on this trip and I was expecting this to be one of them.

People finished wolfing down their breakfasts in the beach cafe and assembled by the bikes. Simon called for hush and everyone gathered round The Crew (sort of) for the morning ‘briefing,’ which, because it was delivered by Simon, wasn't all that brief - but it was entertaining. Over the next ten minutes we got the usual advice about not travelling alone (

It was during this morning’s meeting that Toby first came to everyone’s attention by winning the ‘Dick of the Day’ award. It was inevitable, like a law of nature. Toby, with his tangential take on life was simply wired up to get himself into a pickle. By the end of the rally, then, no-one was surprised that he had won the award several times.

He had come out to join the rally with his mate, David. Toby and David quickly emerged as two of the ‘characters’ on this year's rally, a spectacularly entertaining double act who were rarely off everyone else's radar. Love 'em or hate 'em, you couldn't ignore them. In the coming weeks, their experimental approach to almost everything livened up the days’ riding and provided much of the evenings’ entertainment.

Toby

Simon had overheard a conversation the previous night through the thin plywood walls which divided the beach huts. In the neighbouring hut David and Toby were almost helpless with laughter as they talked over the day's events. Toby had brought his sleeping bag to Palolem on the bike with him, as we all had. It was a bulky, old-fashioned looking bit of kit, which he had bought at the last minute. It had taken up a lot of his luggage allowance on the flight and, yesterday, had been a nightmare to get here because it kept falling off his bike. (David had carried it for a while, and it kept falling off his bike, too.) Last night, Toby had unrolled his sleeping bag for the first time, to discover, much to his surprise, that it looked less like a sleeping bag and rather more like a blow-up rubber dinghy.

After the briefing, people went back to their bikes and kicked them into life for the day’s ride. A beautiful and very distinctive roar began to reverberate through the palm forest. Listening to the sound of one-hundred-and-fifty of these elegant little machines rumbling in unison was enough to put a zing in anyone’s blood. I stood there loving everything about this trip so far. And especially the sturdy little Enfields – though they weren't quite so ‘little’ in my imagination any more, now that I'd had time to discover what brilliant machines they were. I looked around for Larry, but he was parked much further back. I would have to wait for him once I got out onto the road. But for now I nudged forward to get a better placing for an early start, and wedged myself in among those close up to ‘poll position’ (competitive? Me?) .

While I waited for the off, I glanced back through the trees to see if I could catch a last sight of my hut and the long line of the beach. I wanted to fix the scene in my memory. I’d really fallen for this place. I could see myself coming back here some time in the future and chilling out. As it turned out, I wouldn't have to wait very long to see my hut or Palolem Beach again. Three weeks later, back in England I was watching the opening sequence of the latest James Bond film - and there it was: my hut! large as life, snuggled up against the edge of the trees, with JB racing past it in full pursuit of someone or something.

One of the crew members was suddenly pointing and waving his arms. I had no idea what was going on. The bikes in front of me started to move over to one side or another, leaving me a clear line onto the track ahead. Nothing was coming up from behind. I hung back for a few seconds then, in a moment of impulse or impatience, went for it, kicking the Bullet into gear and riding down the quarter mile of sandy, winding paths among the beach huts and shacks to the main road. At the road, I looked back. Nothing. No-one had followed. I was alone. Whoops! So I parked up, and chatted to the film crew positioned near the gates and waited with them for the 'grand exit of bikes' - which didn’t happen for another ten minutes. It was the first and only time on the rally that I was anywhere near the front.

I slowed to let others ride past till Larry came by and then set off with him at a fair pace down the narrow country roads. Houses and people crowded in on us thickly. India is densely populated and coastal Goa is no exception. Villages followed one another with hardly a break between them along the roads. On either side of us locals were coming and going, walking up and down. Children, togged up in immaculate uniforms, were making their way to school. Small family houses were interespresed with very impressive looking villas or recently built blocks of flats. It was all very dusty and, in places, a bit thrown together; the roads were cracked and potholed but Goa has the smell of modest propsperity about it. So far I'd seen nothing approaching the extreme poverty you see in Oxfam adverts.

I hadn't ridden far through all this buzzing human activity, when I met the front riders coming back towards me. I never did find out for sure what the road blockage was up ahead of us, but it meant a detour. I turned back and followed the rest. The detour was no big deal in itself - just a matter of a few kilometres - but it totally screwed up my maths for the rest of the day. ‘Beast’ had started out that morning with exactly 2,350 km on the clock. This made calculating distances from our starting point very easy - which was all to the good as I had a mild hangover that morning and I am totally incapable of adding up when I have a hangover. The detour meant that I had to recalibrate. My effective starting figure when working out distances on the route map was now 2,357.4 km. But 2,357.4 km is not so easy a figure to calculate with - or even bloody well remember. Damn! Until the Kingfisher-induced fug wore off that afternoon, I was going to have extreme difficulty in working out where I was.

Twenty km out from the hotel, we passed a petrol station, and to judge from the number of riders who had pulled into its forecourt, it seemed that most of us had forgotten to fill up the night before. I had a fairly full tank but I wanted to check my tyre pressures, so I decided to find the air pump and thought I might as well top up with petrol at the same time.

The owner of the filling station had a gleeful and slightly mad look in his eyes - as well he might. He was running back and forth between the office and the pumps carrying wads of notes. He was having a good day. There were four pumps on the forecourt but there were only two attendants and it seems it takes two attendants to fill a single bike in India. The queue moved slowly, but as always, it was a lovely morning, and no-one but the front runners felt in much of a hurry - and the front-runners were long gone.

The youngsters operating the pump made a great thing of pointing out to us that the gauge read ‘0’ before they started filling the engine. Clearly they were familiar with the Western belief in the wholly dishonest nature of all ‘foreigners’. But the task of filling our tanks was carried out quietly and smoothly. When it came to pumping up my front tyre it was a different matter. The queue for the air pump was not so long, but inflating tyres was clearly a more complex process. It took four grown men and a lot of shouting and waving of arms to ensure that my tyre was correctly inflated. In a country with vast levels of unemployment, you often find this kind of ‘job-sharing.' Wages might be low but at least everyone has something to take home to the family at the end of the working day.

A long wait at the Oil India petrol station. You get the impression that most Indians

do not understand the meaning of a word like 'hurry.' The guy in the balaclava near the lampost

is Andrew, one of the doctors. At home he volunteers as a speedway medic.

Another six kilometres up the road we ran into the border check post. We were about the leave the tiny tourist state of Goa and enter Karnataka - ‘Real India’ as someone described it. Goa is relatively europeanised and the lack of serious poverty has a lot to do with the tourist trade. I was told that once we crossed over the border, that would change.

The check post was no more than an informal barrier across the road - permanently raised - with a sleepy attendant in military uniform standing beside it. It was there just to make a point rather than stop the traffic. What I wasn’t expecting was the reception committee on the other side.

About twelve guys in formal business wear – immaculately pressed striped shirts and well-creased trousers - were standing in a row, supporting the poles of a huge banner. Several others were holding up a smaller banner at waist height. Both banners read, “Welcome to Karnataka.” As each car or bike passed through the barrier a portly chap with a mature beer gut stepped forward, wreathed in smiles. “Welcome to Karnataka, sir,” he would say, repeating the mantra for what was, no doubt, the umpteenth time that day. And as he made his greeting, he presented the driver or rider with a single red rose. Like Larry and Hash and most of the other Enduros, I had bike gloves on. So, with the most meticulous care, the guy leaned over and attached the rose to my armour, before standing back and waving me on.

My guess is that he and his fellows were members of the Karnataka state tourism board. We came across a number of such worthies in the different states we visited. I was very tickled by this greeting. It was just so… Indian! I tried to imagine a reception committee of Round Table small-time businessmen waiting for me with a budding rose as I crossed the county border between Hertfordshire and Bedfordshire back home in England. “Welcome to Bedfordshire, sir," they might say ("Enter our beautiful county and spend lots of money.") No. No way! It wouldn't happen like that. The most you might find would be a couple of locals leaning over their fences shouting, “Bloody bikers; bugger off back where you came from.” That would be more like it.

I was in a very happy mood as we rolled down the wide open highway beyond the barrier. Larry, and I were riding at a lazy 45 km per hour. We crossed a bridge over another broad, palm-fringed river, took a sharp 300 degree turn, rode along beside a canal then ticked along down a tiny tarmac road at 10 miles an hour. The road ran right through the neat and tidy village of Idgundi. It was so narrow I was sure I was going to hit something - or someone. We squeezed our way past old men and sacred cows, sleeping dogs and excited children. Small inconsequential details took on a strange significance and lodged themselves in my memory: a busy, staggered junction; an old man with a stiff leg; a tumble-down grocery shop; two women in a telephone hut; the vivid blue of a wall; the doleful eye of a cow as it ambled past. All these details flashed brilliantly for a second into my consciousness before melting away into memory. They seemed no more than expressions of the bright, sunlit world around me, part of my happy mood. A bit of me wanted to stop the bike, to talk to people, to move closer to their lives and to the things that they made their lives out of, but the rest of me carried on riding. I knew that if I stopped, even for a second, and engaged my mind with detail, the spell would be broken and my blissful but delicate mood would be shattered for good.

Detail aplenty broke in on my thoughts at the next turning which took us back (briefly) onto a busy road and demanded total concentration. The world changed abruptly. The flow was gone, but my happiness remained. We followed some lovely twists and turns on a beautifully cambered road that swung gracefully downhill, through sparse and delicate woodland.

Well I've got to fess up to this one. I've never carried much weight, but I lost a lot more in India

thanks to having to eat a lot of things I am allergic to. It happens every time I go abroad. So this is me

looking like a 15 year old boy.

The world changed again, and we were riding on narrow, poorly surfaced country lanes sweeping along among grassy levels and bits of scrubland. A broad river came into view, and flowed beside us, almost lapping the road. Here and there it briefly turned away or widened into empty marshland. We stopped among a lonely, watery landscape to look about us and take some photographs. A solitary woman in a brilliant red and yellow sari crossed a distant causeway among the river channels. And around her - flowing water, open sky, a little solid earth and the infinitely mournful cries of river birds.

Further up the road another Enduro had stopped and was gazing silently at the view. We said, hello, and he asked me to take a photograph of him against the watery background. His name was Hasham. I hadn’t met him before. He told me he was Indian by birth but had lived in Northern England almost all his life. We stood together for a long while drinking in the scenery. Before we set off again, Hash asked if he could ride with us. We said yes, of course. Then we stayed together till the end of the rally.

A few kilometres further on, we stopped again by a huge temple standing in the middle of a field. And again by another distant river. Other riders stopped too or passed on by. Some stood up on their pegs to catch the view, or waved as they passed. Apart from the occasional Enduro and a few people on foot going to and from the fields, we were alone on this silent country road.

It was while we were standing, wathcing the waters of the river slowly sliding by that we had our first encountner with Ali and the camera to which she was firmly attached. Ali was a kind of ‘unofficial photographer’ to the rally. She hitched pillion rides from the Enduros all along the route, stopping off here and there to photograph the scenery or the bikes and riders. She had got herself dropped off by the river so that she could capture the view and was now waiting by the side of the road to pick up another lift. She rode with me for a while, snapping away as we went.

Hash and Larry

Twenty kilometres further on and the world changed once more. We were back on broader and busier roads but still among wild country. We stopped for a break and a drink at a wayside stall. Several Enduros were already hanging about drinking tea when we arrived. Larry, Hash and I dismounted, stretched our legs and discretely wriggled our bums. I was already beginning to experience the first symptoms of Monkey Butt, that well-known by-product of riding a Royal Enfield Motorcycle. Monkey Butt isn’t pain as such, just an unpleasant creeping numbness and the uncomfortable impression that your gluteus muscles had taken on the qualities of shrink wrap. “Built like a Gun” had been the motto of the British Enfield Motorcycle company. “Hard as a Bullet” might have been just as appropriate. It was a tough little bike with an even tougher saddle (for which, read ‘plank’).

I didn’t want tea myself. Indian tea is brewed in a large container with milk and an industrial quantity of sugar already thrown in. For someone with a biochemistry like mine, Indian tea approaches the condition of a poisonous substance. I wandered about taking in a few details and feeling a little vague from this morning’s ridiculously early getting-up time and several hours of magnificent but highly focussed riding. There wasn’t much to see. Two painfully thin dogs were pawing over a large pile of vegetable leftovers by the side of the road. Several women were walking up and down attempting to sell garlands of flowers to parked motorists and Enduros. Larry and Hash were deep in conversation. I needed to take a leak. (Now stay with me on this one. It’s educational! If you are walking, camping, cycling or motorcycling in any foreign country, you need to know what the acceptable public behaviour is in the bowel and bladder departments.)

Behind the stalls was a steep, tree-covered slope which dropped away to the village in the valley below. Rising up the slope was a dirt track - an oddly busy little track since, at this end it ended in almost nothing (apparently): just the stalls, the road and miles of rough hill country as far as the eye could see. I found my way down among squat trees and bushes for about twenty yards, hoped no-one was coming and began to battle with all those bloody zips and press studs.

I was already half way through the business when I realised I was not alone. Two women with the same idea, were squatting in the bushes nearby. Now, I have no personal modesty in matters of this kind; I could quite happily dispense with most of the social rules around toilet behaviour, but it doesn’t do to go offending other people’s taboos and sensitivities for no good reason; so I carefully found a tree on the other side of the path and turned my back on the two women. This act of minimal politeness was met by great waves of giggling from the other side of the path. One of the women was Indian the other was an Enduro, but they were both helplessly amused at my behaviour. The giggling was followed by a mini-lecture from the Enduro on the ‘spiritual freedom’ of having a pee in the 21st century. (

The matter of appropriate toilet behaviour was settled for me soon after when an Amercian Enduro asked an Indian chap the whereabouts of the nearest toilet (or whatever euphemism an American would use for a public lavvy). The man looked puzzled for a moment and then, remembering he was in the presence of an alien being, flung wide his arms and replied in classical vein: “India, one very big toilet, sir.” Well, that was a relief! From that point on it was possible to get on with essential business, without unnecessary expeditions or gymnastics.

About nine kilometres further on we saw the junction we were looking for. We turned off the main road and immediately joined a throng of Enduros, Crew members, and an ambulance driver, all of whom were hanging about, taking a break before starting off on the next, very different leg of the journey. Nearby were two signs, one announcing the nearby presence of the Kaiga Power Generating Station ('No Entry') and another pointing in our direction saying simply, ‘Bare.’

This was it! This was the unmade road I had been looking forward to. The Enduro India Crew had really done a lot of work on it. As we stood about, glancing up at the steep, folded hillsides all around u, Simon told the tale of how they had found it. His story went like this. In their search for some really great rough-biking roads they had begun by ransacking the shelves of Indian Libraries. But large-scale road maps of India just do not exist and local roads are known only to local people. When they found no decent maps of any kind on library shelves, the Crew turned their attention to the universities. They contacted a number of academic departments until they found a professor of geography, who had some old Ordnance Survey Maps of India from the time of the British Raj. (One thing the British have always been very good at is making maps. It is practically an obsession. The old OS maps are some of the best ever made, anywhere).

With the help of the OS map, The Crew identified the old Bare Road as a possible candidate for what they wanted and went to take a look. It was perfect, they decided, but needed a lot of work to make it passable for bikes. When they first found it, it was thoroughly overgrown. To get through on that first occasion they had to lift their Enfields over fallen trees and hack their way through the undergrowth. They got permission from the Karnataka government to open it up. It took them several years to clear it and even now they still have to take chainsaws up there every year just before the ride.

It was briefly perfect, Simon said. Then things started to go wrong. As soon as the road had been cleared, the Karnataka government started to ‘improve’ it. At first The Crew tried to explain this was not what they intended, but then realised that the government was seizing the opportunity to turn it into an escape route for the nearby Kaiga nuclear power station in case of an accident. Not so reassuring! Simon laughed. “Nothing happens that fast in India and so far the improvements haven’t progressed very far. The road is still brilliant,” he said.

Riders began to power up. The ambulance driver got into his cab. I lingered for a moment to take a few more pics, then set off behind him. Big mistake!

For some several hundred yards the Bare Road ran along the open hillside, still reasonably surfaced. Then suddenly, as can happen even on conventional Indian roads, the tarmac ran out and was replaced by sandy soil and bare rock. The ‘road’ turned a corner and plunged into the dense hillside forest. The surface dust must have been a foot deep in places. This was totally unexpected. Yikes! I had some hairy moments in those first few minutes. I thought I was going to lose the bike at least a dozen times, and twice I was sure I was going plunge off the road and down the side of the hill into the trees. If anyone had seen my face during that time, it would have been worth a photograph. My pupils must have dilated with shock because everything suddenly went very bright. But again, the Enfield coped very well. It was far more planted and handled better than I could ever have hoped for. I didn’t go down; I didn’t go over the edge, and that began to give me a little confidence. Gradually, I recovered from the mire of panic that was drowning out my thoughts, and got control of my riding. I convinced myself that I was going to survive.

However, the track was not the kind of place to find yourself following close behind an ambulance, especially on a bike. I was riding into a total sandstorm thrown up by the vehicle's back wheels. I could see no more than a couple of inches in front of me. And I couldn’t overtake because the ambulance was occupying the whole width of the track. In any case, every physical and mental function I had available was still concentrating on staying upright. Overtaking would have required more presence of mind than I could muster just at that moment.

But I had to do something. If this goes on much longer, I thought, I’m going to finish the day travelling in this bloody ambulance as a passenger. The image of riding through all that dust for the next god-knows-how-many kilometres grew in my mind and became so vivid that suddenly something inside gave way.

I am usually fairly even tempered but I was now seriously p1ssed off. And there is nothing like being p1ssed off to help you get over inhibitions or anxieties. So the moment I saw the tiniest gap opening up between the ambulance and the edge of the road, I didn't think, I just did the Indian thing – I jammed my thumb onto the bike’s horn and dived into it. I had just enough space to stay on the road with my bar end occasionally scraping against the side of the vehicle.

Stupid? Foolhardy? I don’t know. But I got past the ambulance with a delicious sense of aggressive determination churning in my belly. And as I passed the cab, I was whooping at the top of my lungs. The driver was laughing and gave me a thumbs up. As soon as I was clear of the big lumbering four-wheeled thing behind me I rolled on the throttle and tore up the track. I’d passed some kind of psychological barrier, one that was to give me a different perspective on riding for the rest of the trip - and beyond. (Now, back in England, I realise my riding has taken a quantum leap forward and is freer and more confident than it ever was in the past. One moment. That's all it took.)

A sense of present reality did eventually penetrate my skull again and I slowed a little to make my way up the long track, past little waterfalls and over fording streams. The track markedly improved the higher it got, until it turned back to solid earth, strewn about with small stones. Down in the valley to my left, dumped bizarrely in the middle of the jungle, was the Kaiga nuclear power station. I got an occasional glimpse of it, but paid it little attention. The amount of energy that was being generated down there among the trees was nothing to the sheer adrenalin charge that was zinging away up here on the Bare Road.

I was still experiencing the tail-end of that adrenalin rush and feeling that I could tackle anything when suddenly up ahead the road surface changed again. When Simon had said that, “they were improving this road,” he didn’t mean it in a general sort of way, I suddenly realised; he meant literally that ‘road engineering works are taking place at this very moment as we speak.’ Overlying the dusty red soil, up ahead, were several hundred yards of newly laid hardcore: sharp hunks of broken stone up to four inches across, not yet pounded down and not yet settled into some sort of stability.

“You’ve got to be kidding!!!”

But no, this was for real. Adrenalin is amazing stuff. The manic glee of that first rush was now all but gone but the determination remained. I put my head down and hoped for the best. I just couldn’t have imagined myself doing that three days ago.

‘Looseish arms, even throttle, let the bike pick its way…’ I remembered the advice a friend had given me back home, and I did as I’d been advised. Once again I was surprised at how well the Enfield coped. Great bike! In the end it was me that funked out. About two-thirds of the way across, I fixated on the guys who were watching from far side of the stones (including Simon, who was laughing his b******s off) and suddenly I got all self-conscious. Immediately, I stalled the bike and then couldn’t kick it back into life. It took me about a minute to get the engine going again. And as I stood there, thumping away at the kick start, I was watching some of the other guys going by. The most successful ones, I noticed, kept the throttle open and took it all at a fair speed. OK, if that’s the way to do it… Well, it seemed to work. I cleared the hardcore and rode onto the bridge at its far end.

Among those watching from near the bridge was Ali. She was crouched down to one side of the track with her camera, recording everything that happened. We learned about Ali over the next few days. Wherever there was a likelihood of some dramatic event; wherever there was a nasty corner or a sheet of loose gravel; anywhere where there was likely to be a tumble, there you’d find Ali with her camera, waiting patiently for the inevitable. When she wasn’t sitting it out on dodgy corners, she’d be riding on the back of some guy’s Enfield, facing the wrong way, with her long legs and arms at all angles, and her camera snapping. If there was a good camera shot to be had, you could rely on Ali to be there to find it.

Ali (extreme left), always on the alert for a juicy spill